What Materialists Reveals About Love, Money, and the Myth of the ‘Broke Boy’

Materialists has ignited debate over why poor men are so easily dismissed in modern dating culture, and what that cruelty reveals about how we measure worth

Caught in the crossfire

The internet has a way of flattening men. If you are not tall enough, you’re dismissed as short. If you are not wealthy enough, you’re a “broke boy.” Somewhere in between, entire personalities are erased, their value measured not in love or humor or kindness but in digits on a pay slip. It’s a cruelty so ordinary we barely notice it anymore.

Celine Song’s new film Materialists has tapped directly into this cultural reflex. The drama follows Lucy (Dakota Johnson), a young matchmaker, as she wavers between two men: Harry (Pedro Pascal), whose bachelor pad is worth eight figures, and John (Chris Evans), a struggling actor living in a rental flatshare. The triangle is familiar, but the response has been striking. Online, the film is not being debated for its story or performances so much as for its broke male lead.

READ MORE: Sterling Beaumon Is Playing Hollywood on His Own Terms

Letterboxd users have called the movie “broke man propaganda.” Others, with likes in the thousands, declared: “Broke people should never laugh.” The implication is blunt: to be poor and male is inconvenient and disqualifying.

Celine has rejected this interpretation outright. “Poverty is not the fault of the poor,” she said, calling the label of “broke boy” cruel and classist. What unsettled her most was not the meme itself but how easily audiences accepted it, as if economic status alone determined whether a man could be worthy of love.

The dating economy

That reaction reflects a broader shift in dating culture. Online discourse is saturated with advice from “female dating strategists” and “tradwives,” each reinforcing the idea that the ideal partner is a wealthy one. Even in progressive circles, the message is softened but unchanged: women want someone “stable,” someone “established,” someone who earns. The “broke man” is cast as financially limited and fundamentally undesirable.

For men, this is a particularly sharp blow. Masculinity remains closely tied to financial success, and men without it often internalize failure as a lack of worth. Research shows that husbands whose wives out-earn them are more likely to experience depression, not only because of income disparities but because of what those disparities symbolize. Under this logic, poverty becomes emasculating.

The irony is that most young men are broke, or at least precarious. Debt, rent, and low wages define early adulthood. Yet these years, supposedly when relationships are meant to be built, now serve as grounds for rejection. Struggling men are seen as cautionary tales.

A different kind of wealth

This is where Materialists pushes back. John may lack wealth, but the film frames him as deeply connected to Lucy in ways money cannot replicate. Celine insists the only true non-negotiable in love is love itself. That conviction may sound naive under capitalism, where financial security shapes everything from healthcare access to housing. But her point is less about ignoring economics and more about resisting the urge to collapse people into them.

The language of “broke men” is a class judgment disguised as preference. It converts structural inequality into personal defect and erases the humanity of those who cannot buy their way into desirability.

Still, the dilemma lingers. If love is stripped of financial security, is it enough? If money is stripped of intimacy, is it hollow? Materialists offers no final answer, only the reminder that to choose between the two is not just a personal decision, but one shaped by the culture, and the economy, we all live in.

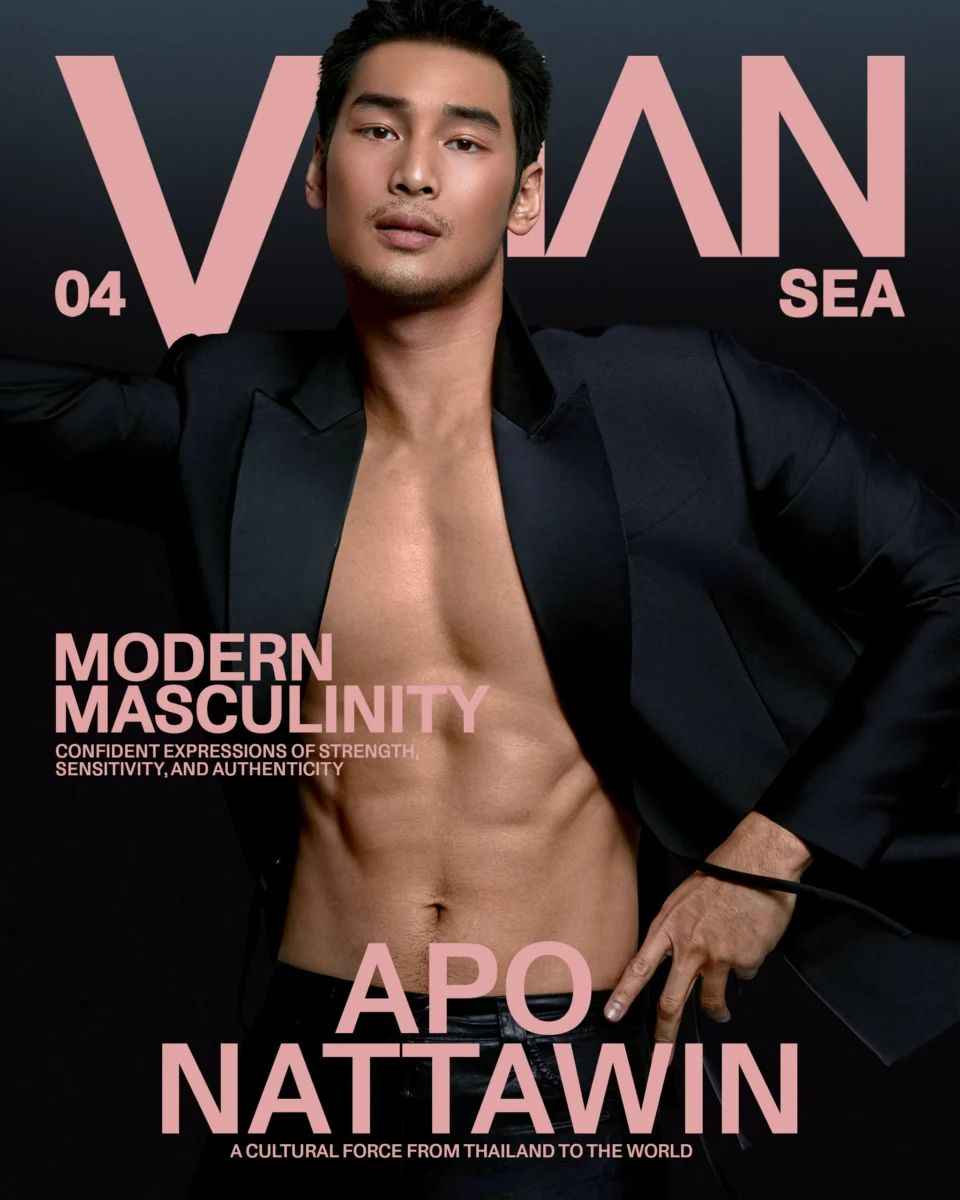

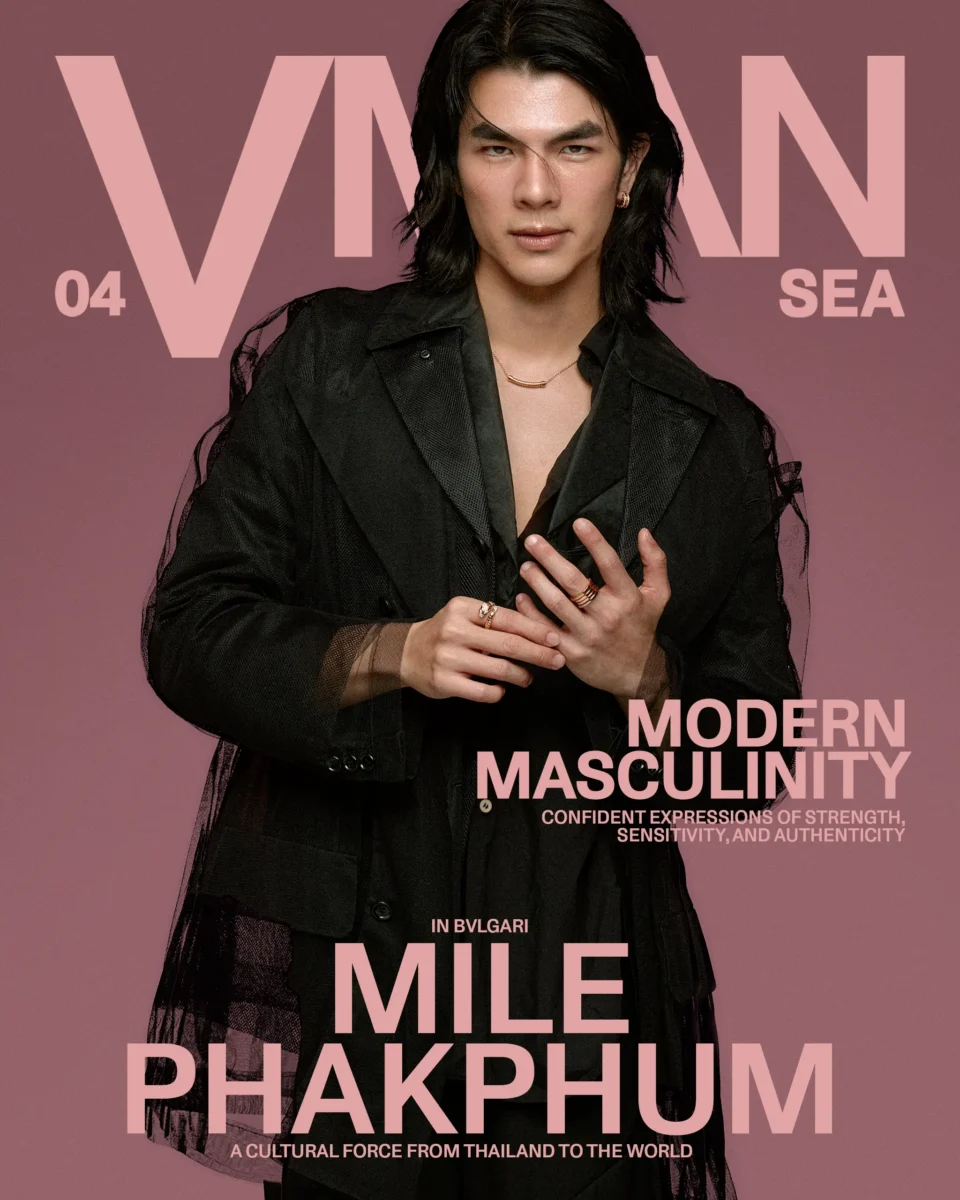

Photos courtesy A24