Why Frankenstein Won’t Stay Dead: The Cultural Resurrection of a 200-Year-Old Monster

Three major filmmakers are reviving Frankenstein, reflecting a renewed cultural unease over science, technology, and the limits of human creation

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, her stitched-together creature and the hubristic doctor behind it, will be raised from the slab not once, but three times, in three wildly different incarnations.

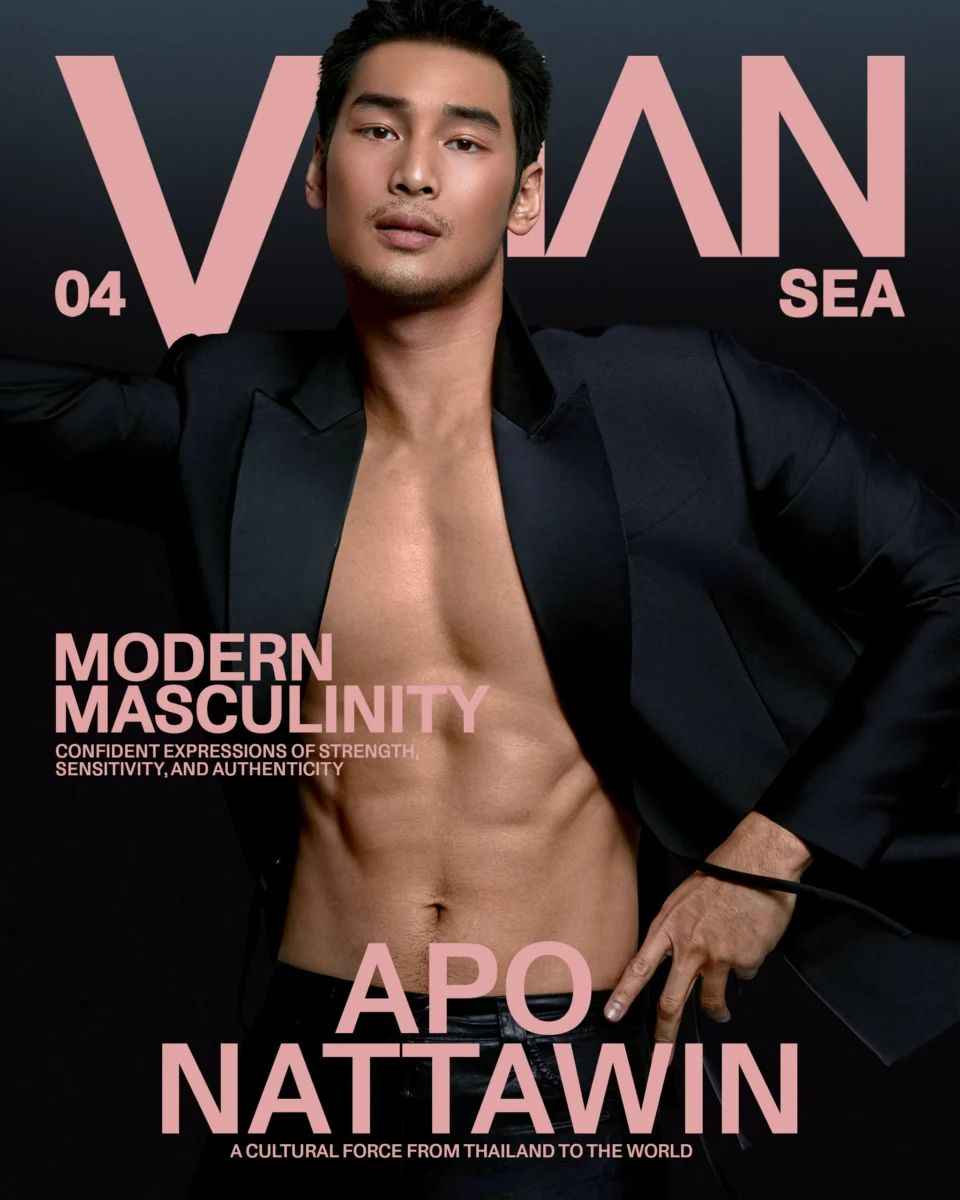

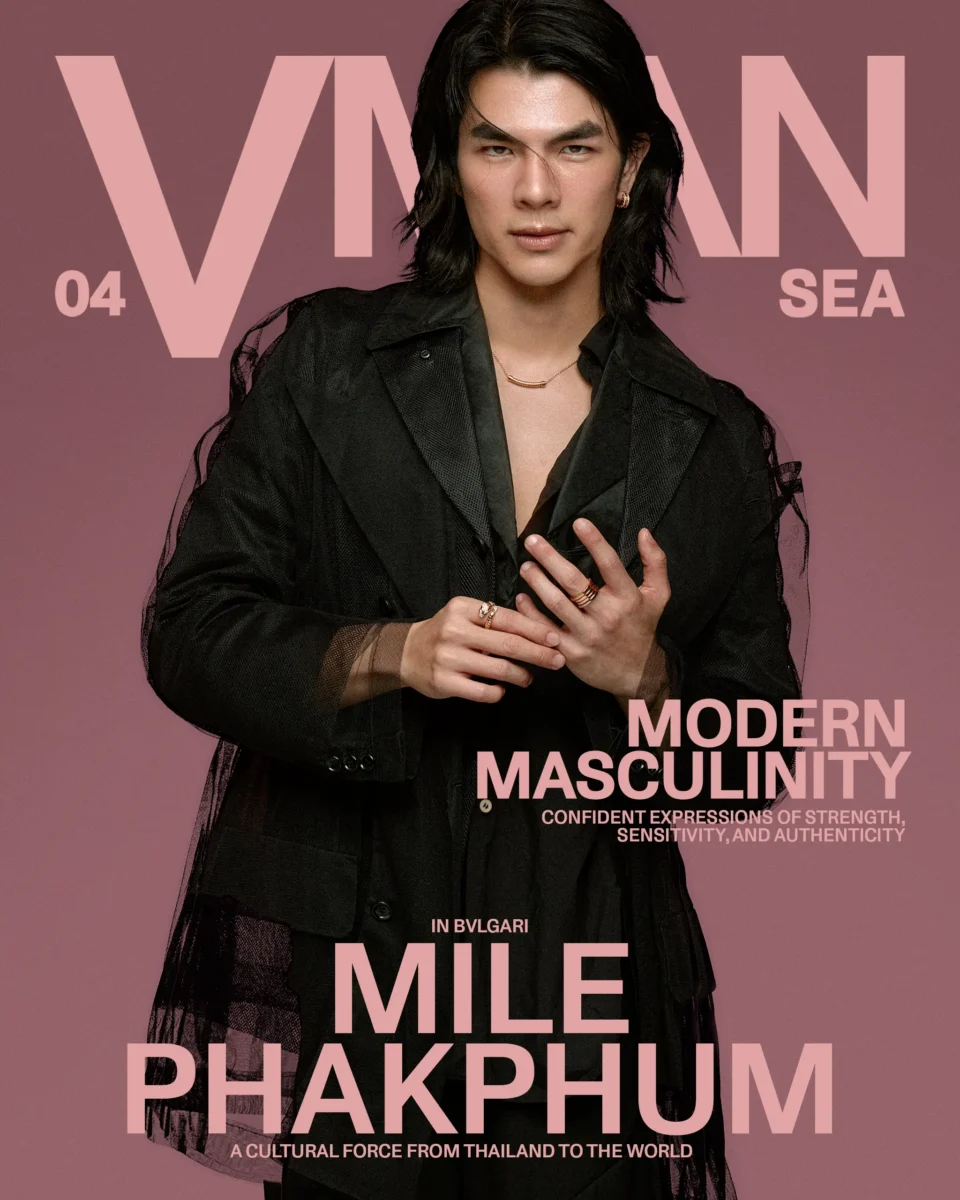

Guillermo del Toro is mounting a shadow-soaked Gothic epic with Oscar Isaac as the doomed doctor. Maggie Gyllenhaal is resurrecting The Bride!, this time with a gender-flipped lens and Penélope Cruz in the role of a creator who refuses to stay in anyone’s shadow. And Romanian provocateur Radu Jude is preparing a sardonic, distinctly European take starring Sebastian Stan that promises more media satire than midnight horror.

The convergence is too strange to chalk up to coincidence. Frankenstein thrives in moments when the world feels a little too modern for its own good, moments when the question What happens if our creations escape us? starts to feel less hypothetical and more like breaking news.

READ MORE: Not Another Teen Movie: 7 Coming-of-Age Films That Actually Get It Right

A monster for all seasons

Mary’s 1818 novel was born of its own cultural panic: the Industrial Revolution’s roaring machinery, a scientific community dabbling in electricity and anatomy, and a growing suspicion that human ingenuity might be clever enough to undo humanity itself. The story caught fire in the public imagination and has since drifted ashore in every generation’s moment of reckoning.

In the 1930s, Universal Studios’ square-headed, bolt-necked monster reflected a world grappling with the rise of industrial modernity and the brute force of the machine age. By the 1970s, Cold War paranoia and new fears over genetic engineering produced stranger, more cerebral Frankensteins.

In the 1990s, Kenneth Branagh’s feverish, gold-lit adaptation emerged in the shadow of the biotech boom. Now, in 2025, the fears are quieter but no less existential: AI ethics, lab-grown organs, climate instability, and the eerie feeling that our digital selves, the ones carefully stitched together from profile pictures and algorithmic preferences, have lives of their own.

Monsters as mirrors

The monster always mirrors something different than we expect. In Mary’s time, it reflected unchecked science and moral hubris. Today, it reflects a black smartphone screen at 3 a.m., a face lit by an algorithm we did not design and cannot quite stop feeding.

The genius of Frankenstein is that the “monster” is rarely the one with the stitched skin. It is the impulse to create without imagining the consequences, innovate without consent, and believe that control is permanent. Mary called it “playing God”; we might call it shipping the update before the beta test is done.

Three versions of creation gone wrong

Guillermo promises the signature melancholy of his best work in his forthcoming Frankenstein, creating a lavish, candlelit world where the creature appears as a tragedy and invites the audience to mourn him. Maggie takes The Bride! further by prying open the story’s gender politics. If Victor Frankenstein built a wife for his creation, who decides her fate, the monster, the maker, or herself?

Radu will likely treat the myth as a dark joke about public spectacle. He reminds us that modern monsters often come designed to be consumed, memed, and discarded by the same audience that once feared them.

Why Frankenstein keeps coming back

Two centuries on, Frankenstein remains the perfect story for an anxious age because it does not belong to any one genre. It is, in turn, a scientific fable, a gothic romance, a social satire, and a tragedy. It can be stripped for parts and rebuilt to fit whatever fear is currently humming in the air, whether it is the crackle of a laboratory experiment or the electric hiss of a server room.

The monster always returns when we feel most uneasy about our own ingenuity and fear our inventions more than any external threat. Perhaps that is why 2025 feels so ready for his arrival. This year’s Frankensteins do not come from graveyard scraps; filmmakers piece them together from lines of code, 3D-printed tissue, and curated personas that outlive the people they pretend to be.

Two hundred years later, we still cannot decide who to pity more: the creation, abandoned and bewildered, or the creator, too proud to admit the thing he made might outlive him. Either way, we are still the ones holding the scalpel.

Photos courtesy IMDB