Matcha on the Move

What was once a distinctly Japanese drink is now a measure of indie-pop cool—but with reports of a global matcha shortage, have we indulged too much?

Why is there a global matcha shortage?

From inside the humble Japanese tea ceremony room, matcha has now migrated toward every health, wellness, and fitness influencer’s cupboard—and its global appeal is just getting stronger.

The Asian culture boom in the 2010s, propelled by K-Pop and Japanese culture, set the foundations for matcha’s popularity in the West. From lattes, cookies, ice cream, to health drinks, the deep, dark green powder not only appealed to new audiences visually, making its way into every Instagram or TikTok feed; it also struck a chord within the health-conscious sort.

Matcha’s rich concentration of antioxidants is said to help with heart vitality, brain function, and cell repair, among others. When the pandemic struck and people started minding their well-being more, the whole world turned to matcha as a type of ‘superfood.’ And since it also has significant amounts of caffeine, cafés and influencers were marketing it as a healthier alternative to coffee.

Matcha transformed from a simple powder to a lifestyle: what was once a traditional ingredient became more accessible. Suddenly, the whole world was partaking of something distinctly cultural, markedly Japanese, and decidedly cool—all while reaping the benefits.

That’s why when well-known Kyoto-based tea companies Ippodo and Marukyu Koyamaen disclosed last autumn of 2024 that they will either limit or stop selling certain ceremonial matcha products, the worldwide reaction was nothing short of catastrophic.

Initially, the Global Japanese Tea Association wasn’t surprised by the announcement. On their website, they cited how production is already a relatively humble operation to begin with: top-grade matcha is still being made in already small amounts via traditional methods. On top of that, the number of farmers isn’t increasing, and those who remain are part of Japan’s aging population.

The leaves used to make it—tencha—also take time to grow. Moreover, it isn’t unusual for matcha reserves to diminish toward the winter months; besides, the spring harvests would eventually come in to replenish the stocks for the upcoming year.

But now we’re in the third quarter of 2025, and that shortage announcement still exists on Marukyu Koyamaen’s website. It’s not just a matter of limited supply; the demand for matcha has exponentially risen post-pandemic, and it’s showing no signs of slowing.

It cannot be denied: how matcha was portrayed on social media contributed to its astronomical demand. The tourism boom in Japan post-COVID also diminished supplies, with many visitors buying in bulk because of lower costs. Exports have also been rising; more than the rising demand from the already matcha-crazed West, emerging markets like Africa and the Middle East are also competing for limited supplies.

So, where does matcha go from here?

Production-wise, many measures are now being explored: encouraging more tea farmers to harvest tencha, and building new farms outside of Japan; creating more stone mills used to grind leaves, among other innovations—though these will take years to develop.

On the customer side of things, you can ask yourself this: would you buy matcha for social media, for its health benefits, or simply because you like it?

Whatever your motivations are, consume with mindfulness and intent. Savor that matcha beverage, and appreciate how it made its way from vast plantations in East Asia to your local specialty shop. Hype should not come at the cost of compromising a cornerstone of a country’s culture.

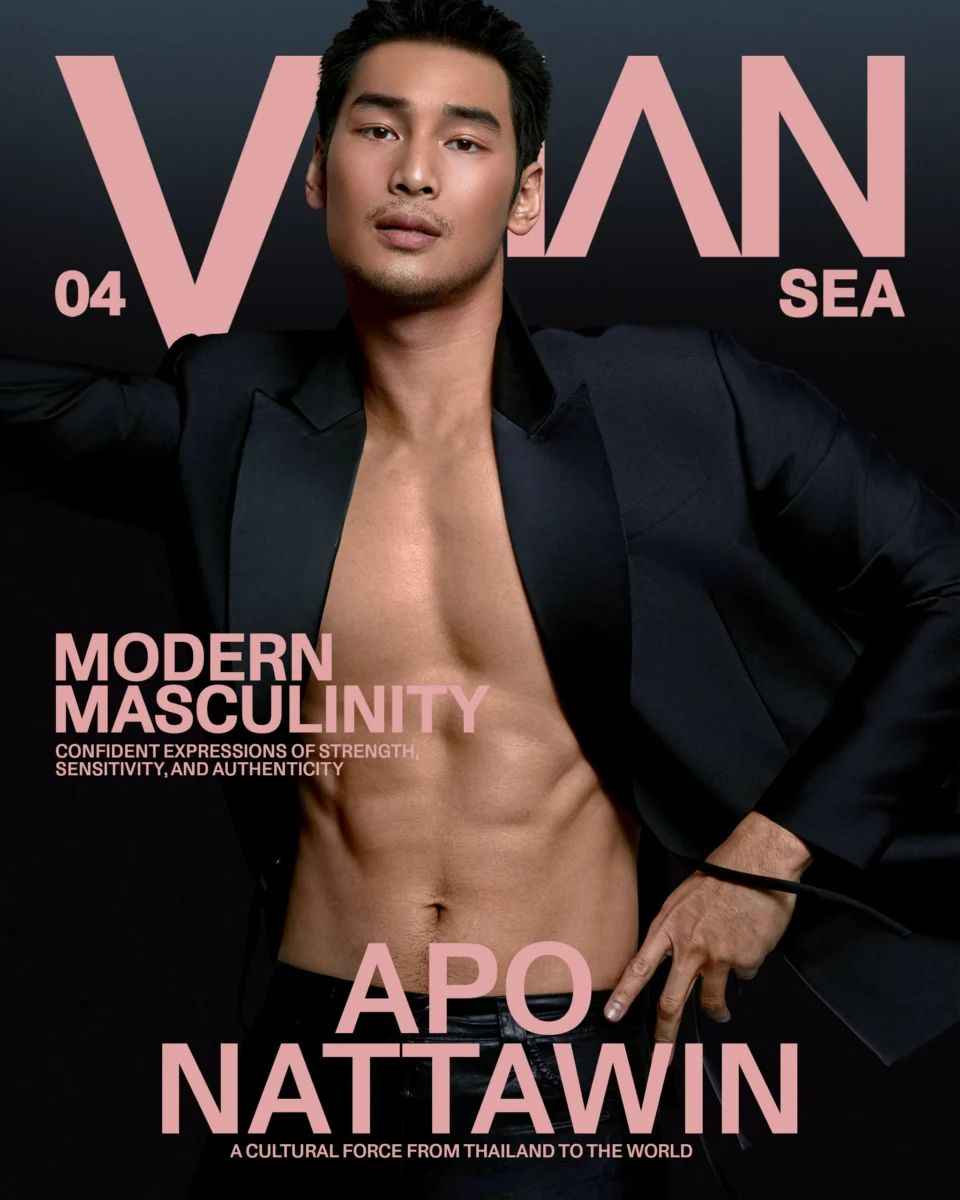

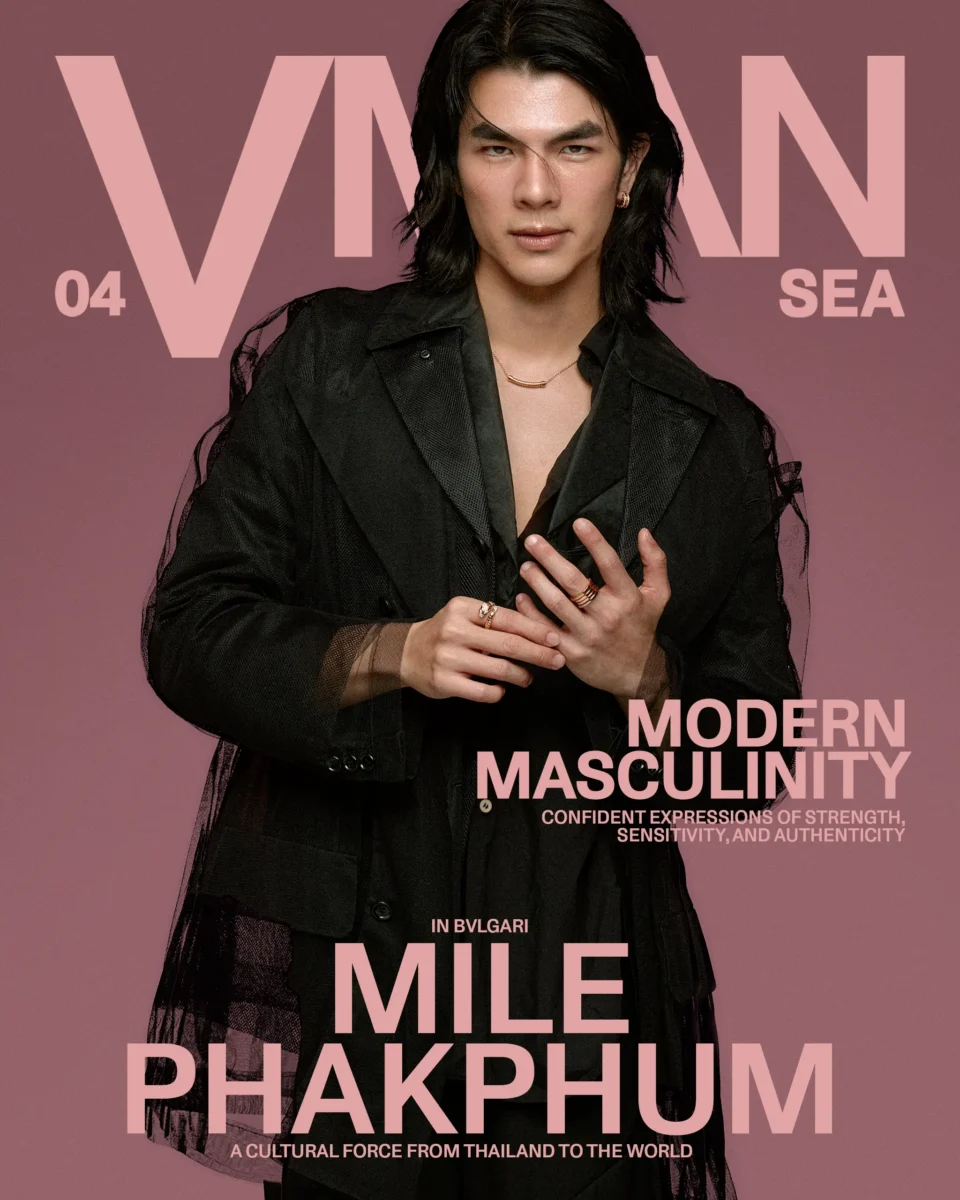

As seen in the pages of VMAN SEA 04, available in print and by e-subscription.

Photography Roman Odintsov