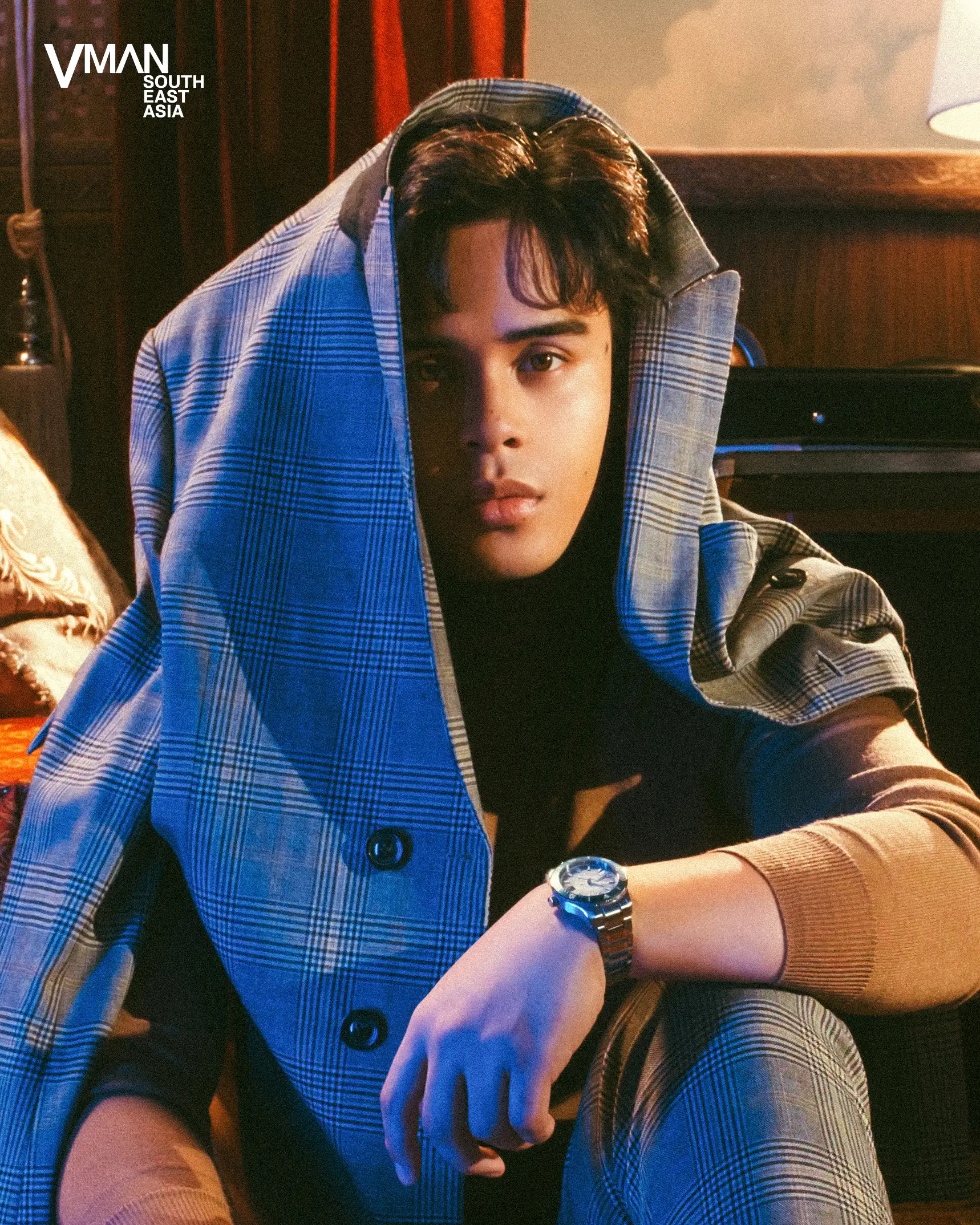

Khalil Ramos Is Making Every Role Count

From a reckless teenage leap into national television to a purpose-driven life in film and theater, the Filipino actor reflects on craft, endurance, and what it means to stay truthful in an industry that rarely slows down

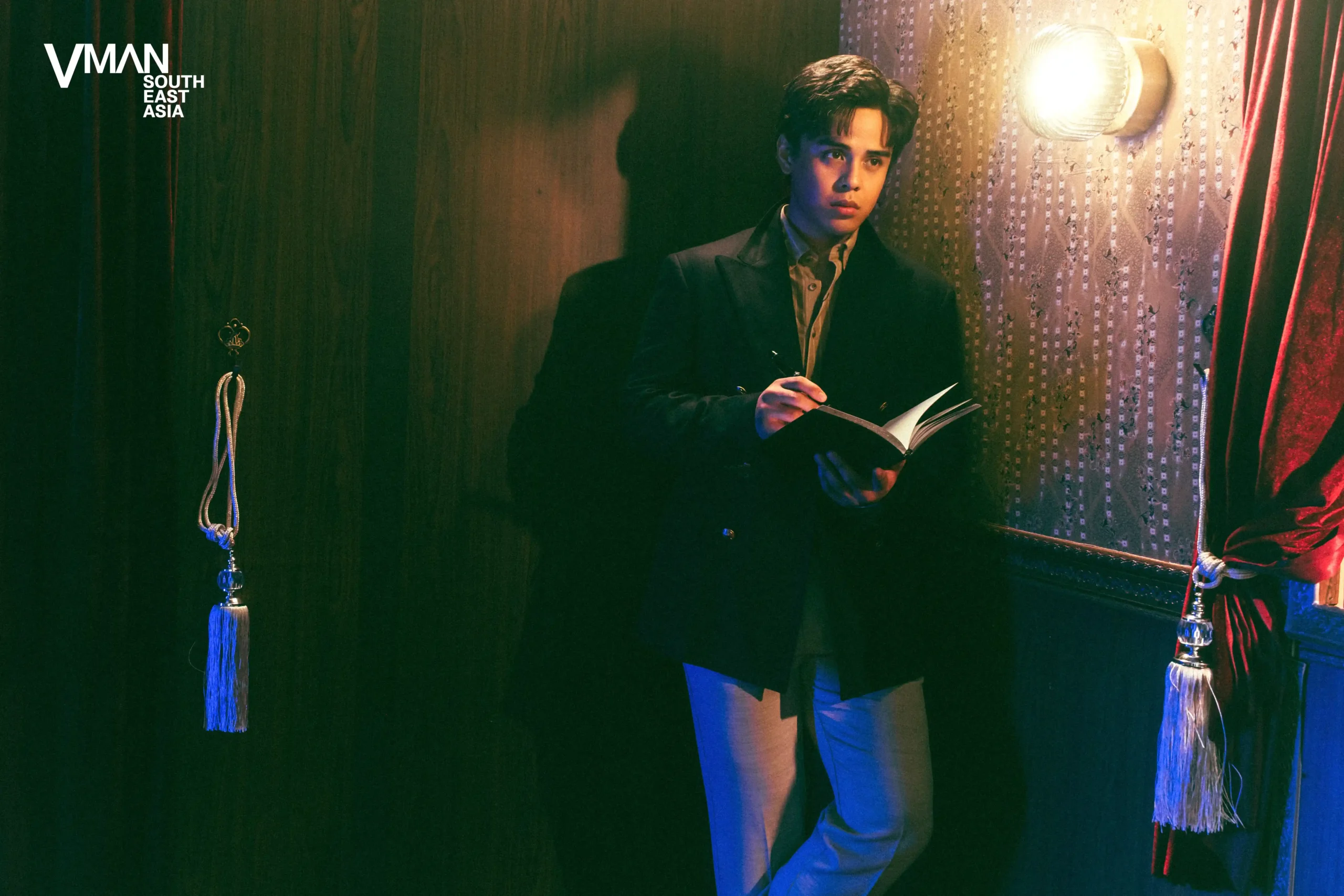

Writing the journey

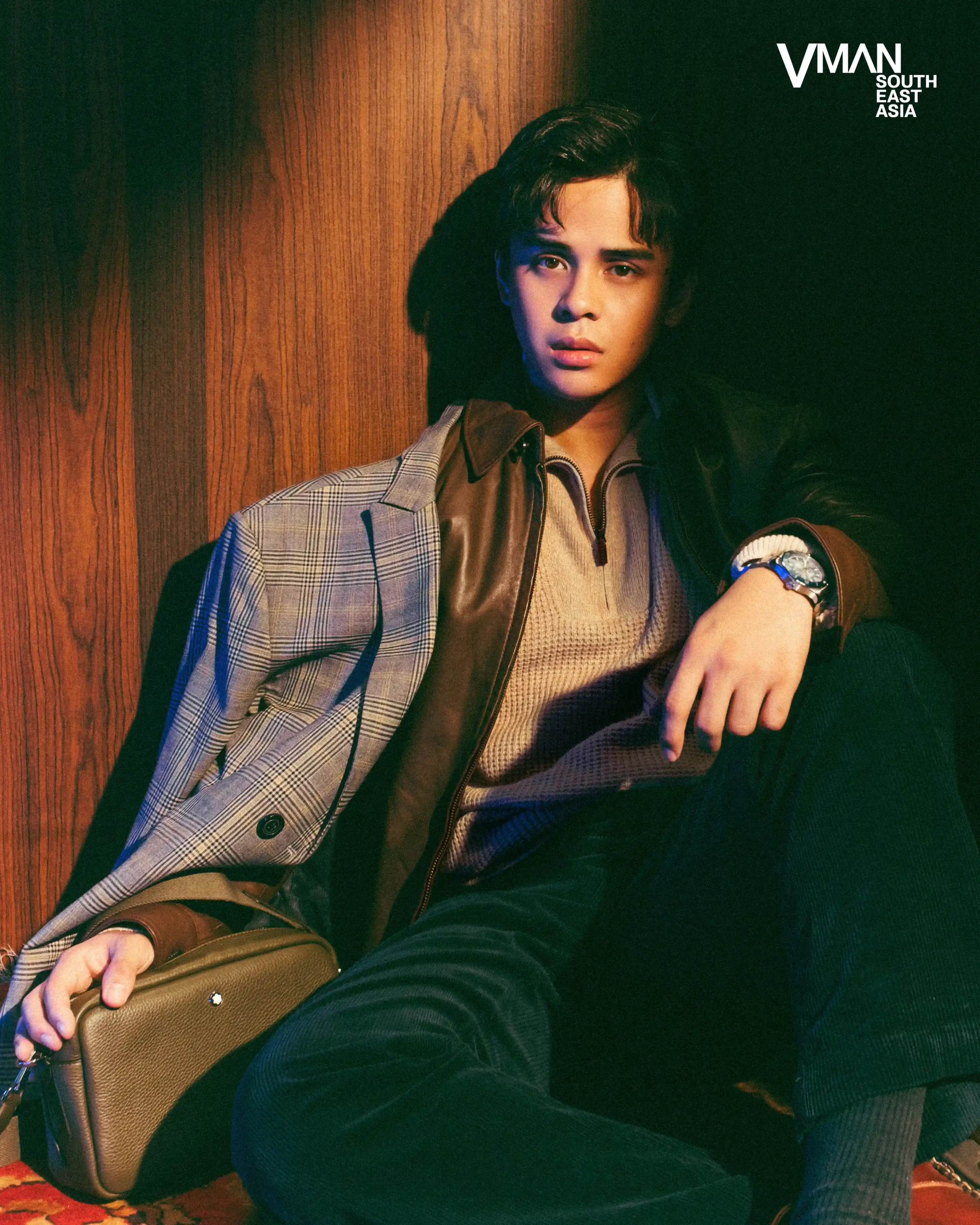

Khalil Ramos boards a train as if stepping into a story. A Montblanc pen rests lightly between his fingers as he traces invisible lines in a notebook, pausing to take in the passing scenery with the wonder of someone seeing the world for the first time.

Inspired by Montblanc’s latest campaign, Let’s Write, in collaboration with filmmaker Wes Anderson, his VMAN Southeast Asia cover shoot captures a meditation on observation and storytelling before the narrative of his life unfolds.

The reckless leap

Khalil remembers being fifteen and having no plan, which, in retrospect, feels like an honest starting point. It was college fair season, the period when Filipino high school students are expected to imagine entire lives from a row of brochures laid out in a gymnasium. He could not.

“When I was there during the college fairs, I had little to no plans of what course to take or what I actually wanted in life,” he says. “I was a very happy go lucky kid.”

He was not academically inclined, he admits. What he knew, even then, was where he felt confident.

“I excelled more in extracurricular activities in the arts. That was one thing I was sure of. I was confident enough in my voice as a singer and as a performer.”

Acting, at that point, was not part of the picture. “I had zero experience and knowledge in acting.”

Joining Pilipinas Got Talent, a Philippine competition reality television show, was not a calculated career move. It was, as he describes it now, a reckless leap of faith. “It wasn’t planned at all,” he says. “The plan for my family was actually to migrate to the US to pursue better opportunities in life.”

His decision changed that. “Because of me, because of my reckless leap of faith, I changed the course of my family’s plans.”

At fifteen, he did not yet understand the scale of what he had done. “I went into it as a guy who wasn’t professionally trained to sing,” he says. “I just knew how to sing and had enough confidence to sing in front of a national crowd.” Only much later did the weight of that moment register.

The industry opened quickly. What it demanded would take years to understand.

Learning the industry’s rhythm

More than a decade later, Khalil speaks about that early period with a mix of disbelief and clarity. He laughs when he corrects himself about when his career started. “Actually, we started in 2011,” he says, then catches himself. “Oh my God, now I feel old.”

The industry he entered no longer exists in the same form. “Light years away from what it was back in 2012,” he says. What once felt fast now feels almost slow by comparison. The digital shift has altered not just how careers begin, but how they are sustained.

“In a lot of ways, it’s easier and difficult,” he says. “It’s easier because the tools are right at your disposal. You can enter the industry with your phone.”

“As long as you have confidence and a thick enough skin to be yourself and express yourself authentically, there’s a space for you.”

What comes after is harder. “What’s difficult is staying. Remaining relevant, remaining true to yourself, and sustaining this as a profession is the hard part.” Speed, he says, has become essential. With the rapid changes, speed is key. You have to adapt quickly.”

The challenge has only intensified with new technologies. “Now with AI, authenticity is blurry,” he says. “It’s easy to penetrate, but difficult to maintain a career in show business.”

That tension between access and longevity has reshaped the way Khalil works, especially in film and theater. Stronger labor protections for artists have improved conditions, but they have also compressed time.

“On set, you’re expected to perform efficiently and quickly,” he says. “Before, we had more time to prepare and work on character. Now, it’s a luxury to get a second or third take.”

The adjustment is ongoing. “You have to be as efficient as possible while still being good,” he says. “It depends on the projects you choose, but it’s a skill I’m still mastering.”

Finding creative depth

Despite the pressure, he believes the industry has matured creatively. “Story wise, material is getting more progressive and deeper,” he says. “In struggle, new creativity is born.”

The pandemic marked a breaking point. “We hit rock bottom when cinemas closed,” he says. The shutdown forced a reckoning about purpose, sustainability, and what kind of work was worth returning to.

When Khalil talks about the artists who shaped him, his answers trace a lineage of seriousness. “Internationally, Paul Mescal, Timothée Chalamet,” he says, then moves backward. “The classics for me are Daniel Day-Lewis, Marlon Brando, Leonardo DiCaprio, Al Pacino. They’re legends for a reason.”

Closer to home, his respect is equally specific. “Locally, Jericho Rosales,” he says. “I worked with Romnick Sarmenta, who is a rare breed and truly a master of his craft.” He also points to his peers. “Elijah Canlas, Cedrick Juan, and many other great actors.”

But it was the film 2 Cool 2 Be 4gotten that changed his relationship to acting most profoundly. “2 Cool was my first exposure to alternative cinema,” he says. “It opened my eyes and made me take my craft seriously.”

“It made me realize the responsibility of an actor, not just on screen but in the messages we tell. It shaped who I am as an actor today.”

Selectivity and purpose

That sense of responsibility has made him increasingly selective. “After Olsen’s Day, I’m very particular now,” he says. “If the motivation is just fame or glamour, it’s a waste.”

His criteria are clear. “Script and story are king,” he says. “That’s where you see the message and intent.” Just as important is trust. “Trust between director and actor is what I value most.”

He understands the privilege embedded in that selectivity. “It’s a privilege to be selective,” he says. “When I was starting, I didn’t have that choice.” Skill development, he believes, brings clarity. “It helps you understand where you fit in the industry.”

Working with someone he is in a relationship with has introduced its own complexity. On LSS (Last Song Syndrome), opposite his real-life partner Gabbi Garcia, familiarity was both an asset and an obstacle. “You’re not starting from zero, which helps with trust,” he says. “But you have to unlearn each other.”

“You can’t just be Gabbi and Khalil on screen,” he adds. “You have to create different characters. Otherwise, it’s a disservice to the audience.” The work required conscious separation.

“We had to learn how to [work together as partners] on screen. Thankfully, our relationship is healthy enough to navigate that.”

Theater presented a different challenge. “I was terrified of anything live,” he says. “That fear became an anxiety.” Saying yes to Tick, Tick… Boom! was an act of discomfort. “But I wanted to improve,” he says. “Theater is the actor’s medium.”

What convinced him was the material. “With Tick, Tick… Boom!, I loved the material and related to the character,” he says. “It was about breaking my comfort zone and building discipline.”

Truth across mediums

Across television, film, and stage, Khalil returns to one guiding principle. “The truth shouldn’t change,” he says. “The approach changes depending on the medium.” Television, he explains, is heightened. Film is nuanced. Theater is performance driven. “But the truth remains the same.”

Burnout, he says, is inevitable. “I’ve experienced many burnouts,” he admits. His response is not withdrawal, but redirection. “I remind myself that creativity is a lifestyle, not just a job.”

When acting feels stagnant, he moves elsewhere. “With photography, with coffee, with cars,” he says. “Right now I’m into overlanding and camping.”

“When I feel tired or burned out in a certain medium, I exercise creativity elsewhere. It re-energizes me.”

Photography, in particular, feeds directly back into his acting. “Acting is about awareness,” he says. “Photography, especially street photography, is a study of human behavior.” Different places offer different sensory experiences. “Different places have different energy, smell, sound,” he says. “That sensory memory helps my acting.”

The connection feels intuitive to him. “Acting is motion pictures,” he says. “Moving photos. It works seamlessly.”

Music, once central to his public identity, now occupies a more modest role. “I can sing,” he says. “But I’m not a songwriter.” He recognizes the current landscape. “The Philippine music scene today is songwriter driven, which I respect.” Music, he has accepted, “isn’t my main lane.”

Seeing life through a lens

Looking ahead, his ambitions have sharpened rather than expanded. “As I enter my 30s, I want projects with a higher purpose,” he says. He names stories about social class, Filipino workers, and contemporary life. Genre-wise, he is drawn to horror. “I’m enjoying horror because it’s evolved. I want to be part of films like that.”

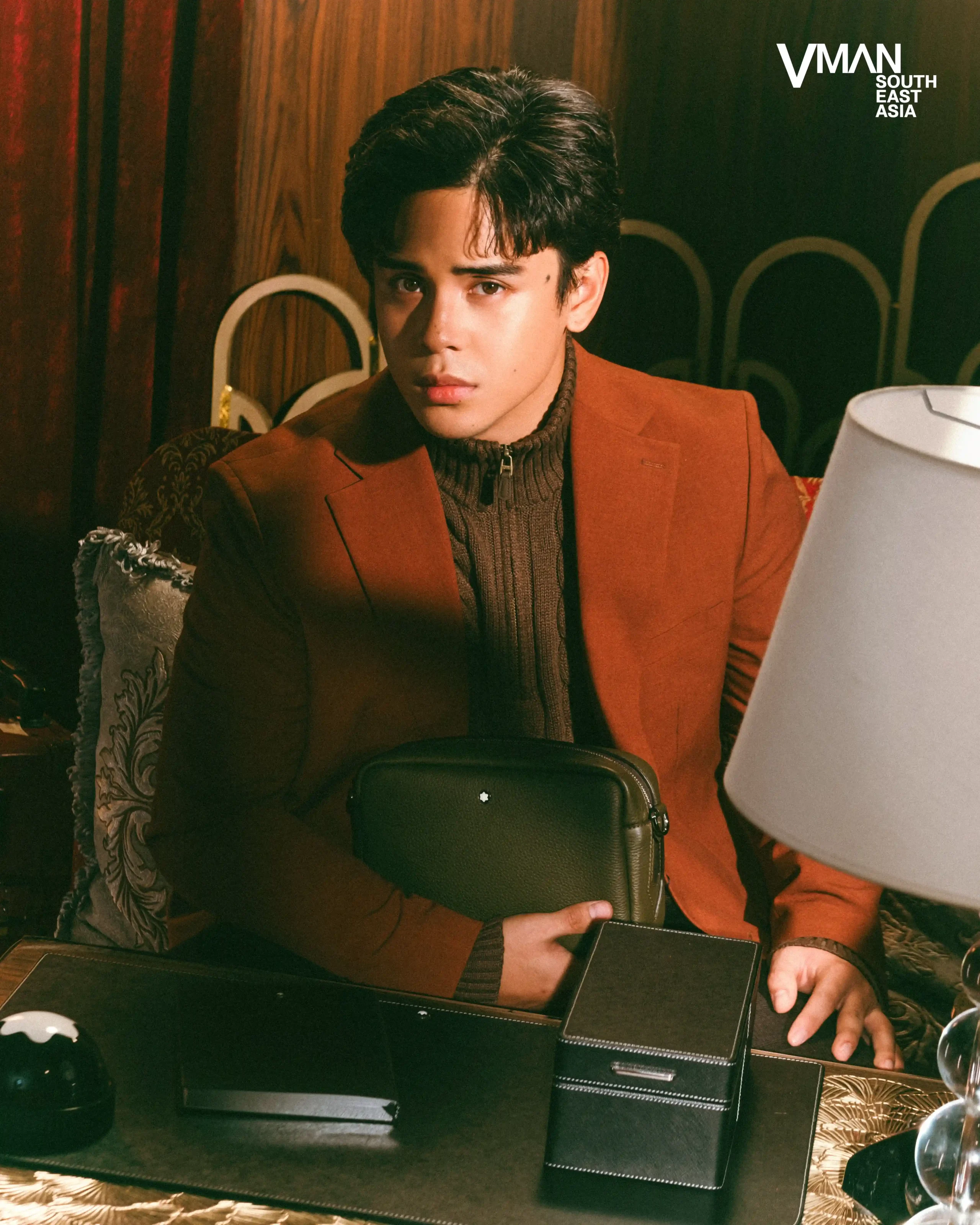

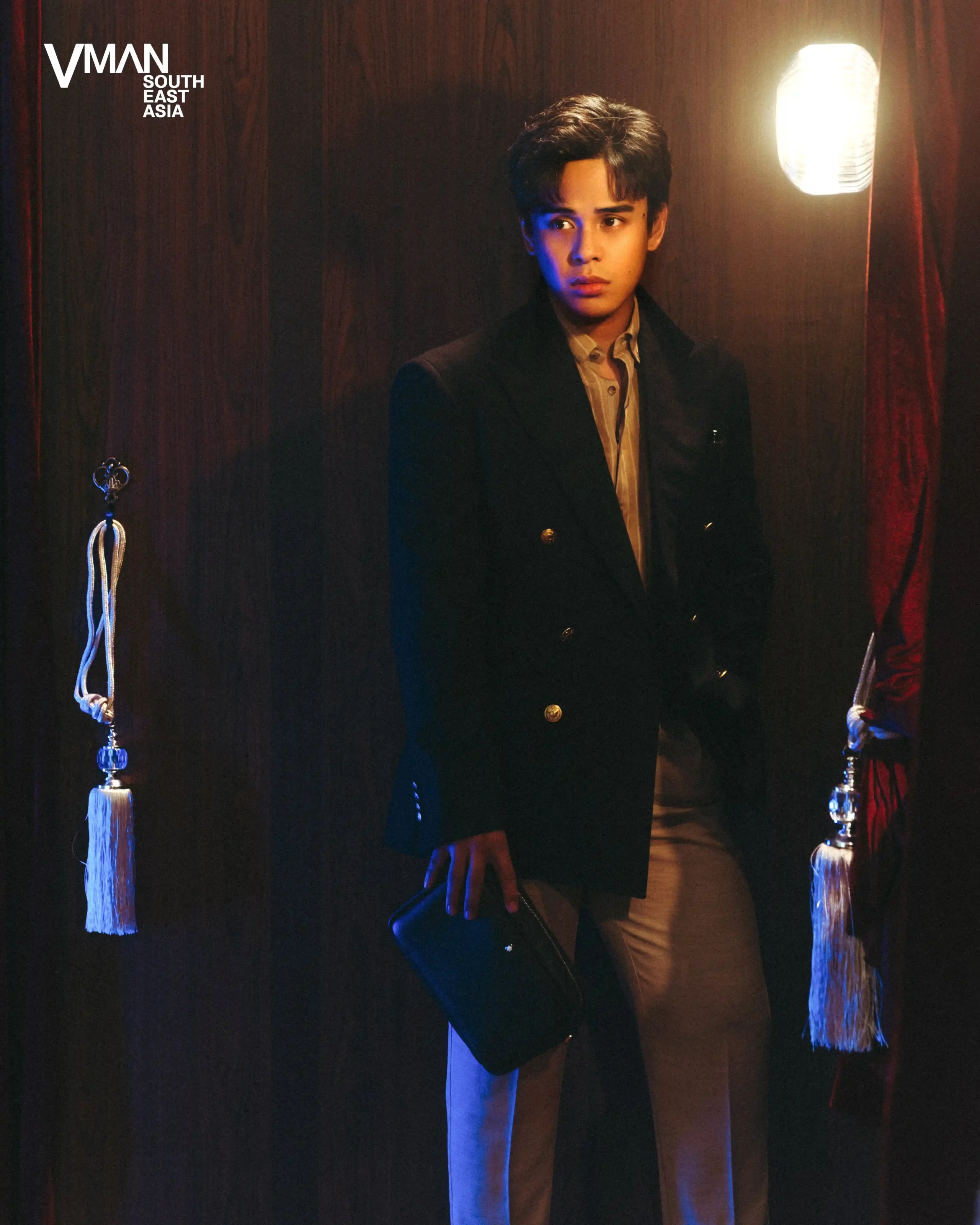

It is fitting, then, that his latest shoot draws inspiration from Let’s Write, part of Montblanc’s ongoing collaboration with filmmaker Wes Anderson.

The campaign centers on a short film set in the Montblanc Observatory High Mountain Library, imagined as both a physical space and a metaphor. It celebrates writing as discipline, creativity, and devotion to craft.

Like writing, Khalil’s career has been shaped by revision, by learning when to pause and when to commit, and by returning to the work with a clearer vision.

What emerges instead is a practice shaped by uncertainty, sharpened by risk, and sustained by the discipline of staying present.

Khalil Ramos understands that longevity does not come from haste, but from attention. The work continues, page by page, scene by scene, each choice set and allowed to last.

Chief of Editorial Content Patrick Ty

Photography Andrea Beldua

Art direction Mike Miguel

Fashion Rex Atienza

Editor Dayne Aduna

Grooming Mac Igarta

Hair Mark Familara

Retouching Summer Untalan

Fashion associate Corven Uy

Production Francis Vicente

Production design Studio Tatin

Design director Migs Alcid

Design manager JL Honor

Associate production designer Jael Faelnar and Mar-Ian Ejandra

Photography assistants JR Baylon and Mario Pepito

Grooming assistants Florante Katalbas and Angelo Torralba

Setmen Mario de Asis Gonzales, Jeron Jamora, and Rafael Calleja

Special thanks Rustan’s PH, SSI Life PH, Sparkle GMA Artist Center, Rochelle Tuazon-Chavez, Caiel Pajarillo, Ysa Solon, Rodelyn Flores, and MC Cruz