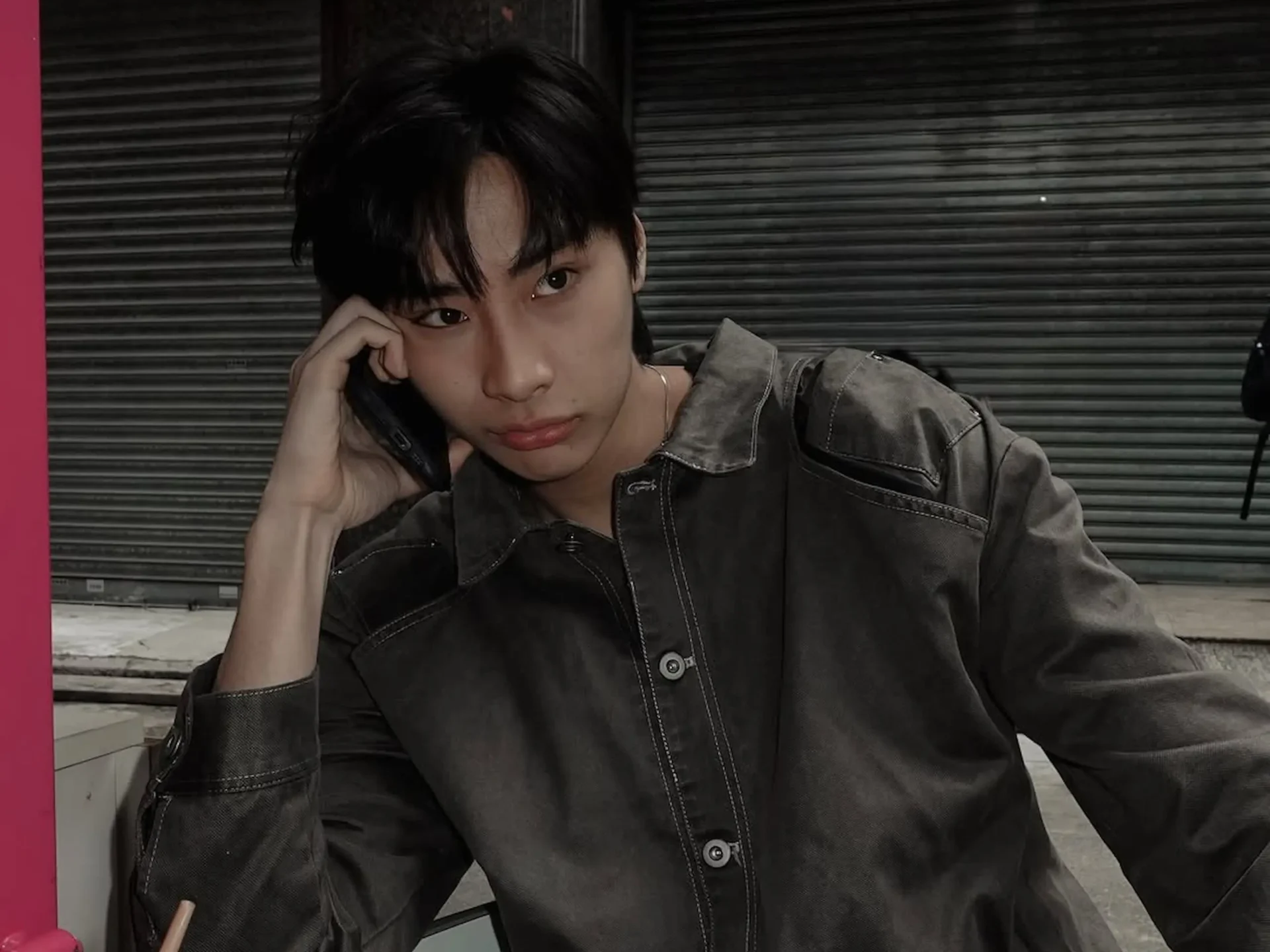

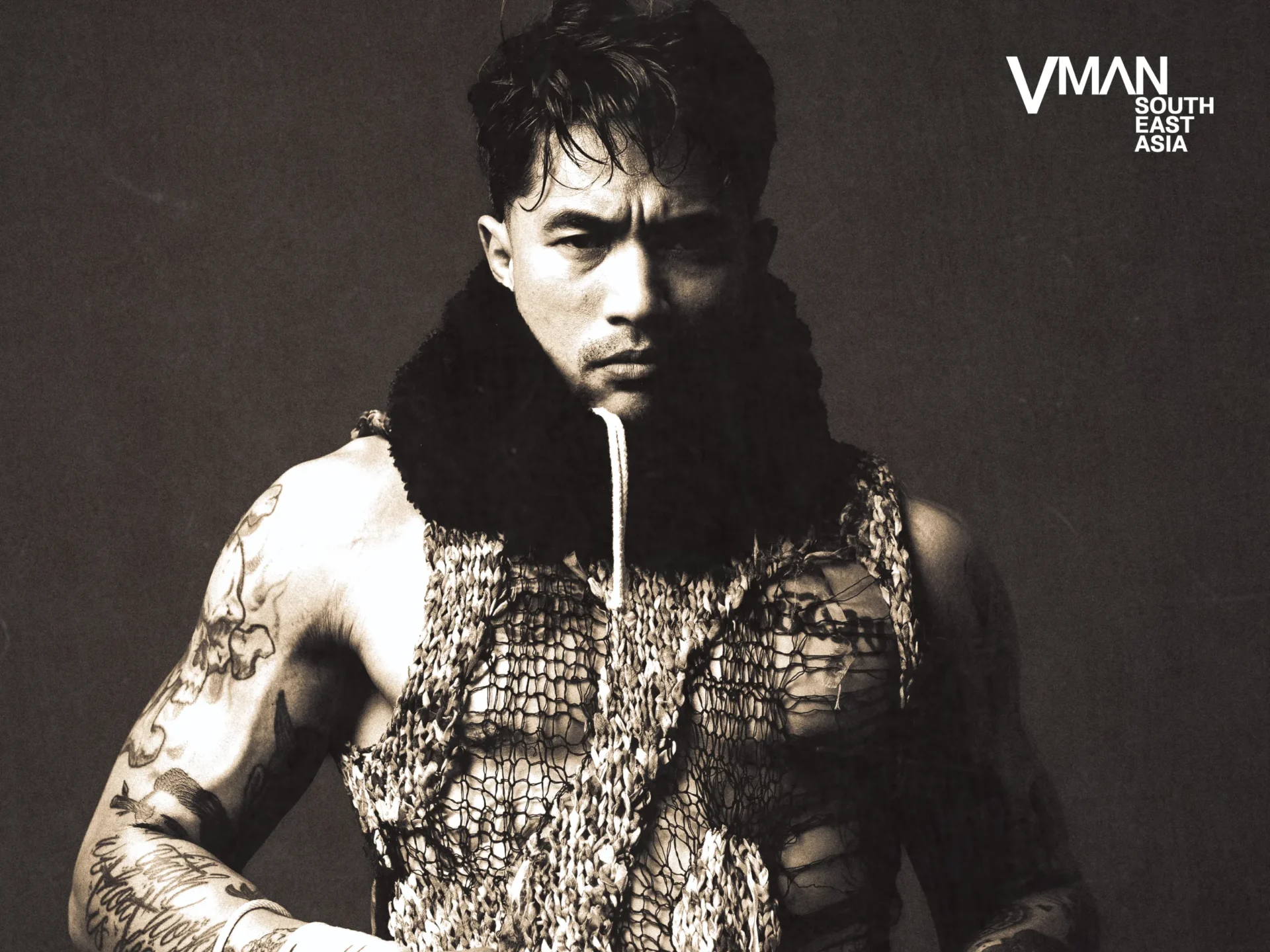

Sterling Beaumon Is Playing Hollywood on His Own Terms

From Lost to indie dramas and the hockey rink, Sterling has built a career on committing fully to every role and creating his own when the industry wouldn’t hand them over

Morning on the ice

On a peaceful Tuesday morning in the city, the rink is almost empty. A few players in mismatched jerseys glide across the ice, sticks clattering against the boards in a rhythm too steady to be accidental. Sterling Beaumon, helmet off, coasts into the corner, leaning on his stick for a breath before laughing at something shouted from center ice. In a few hours, he’ll be back in the city, returning calls about production timelines and audition schedules. For now, he is just another skater. “Hockey’s the one place I can turn my work brain off,” he says later. “It’s great exercise, and taking care of your body helps your mind follow.”

By the time Sterling was 14, he had already portrayed one of television’s most enigmatic antagonists, at least in his younger form. On ABC’s Lost, Sterling’s portrayal of young Ben Linus was not the usual child-actor gig: there were no precocious punchlines or tidy moral arcs. The role demanded a contained darkness, the sort of unsettling stillness that leaves audiences suspicious. For Sterling, it was both a breakthrough and a blueprint. “Lost changed my life,” he says now. “It’s the reason I have a career.”

That was more than a decade ago. Since then, he has navigated the narrow and often treacherous path from child roles to more layered adult characters, a transition that has stalled or derailed many of his peers. He admits that when he was younger, he assumed acting opportunities would always be there. But years of working across television, film, and even voice acting have recalibrated his sense of the profession.

“I’m grateful any time I have the chance to act. As I’ve gotten older and worked in different areas of the industry, I’ve realized what a privilege it is every time I get to be on set.”

Crafting the character

This perspective has sharpened the way he approaches his work. His process varies from role to role, but one constant is a construction of the character’s life outside the script. “I like to know exactly where the character has been, where he is now, and where he wants to go,” Sterling explains. On days when a scene demands emotional weight, he spends hours setting the tone, finding the right music, solitude, and headspace.

His filmography has become a catalog of extremes. He’s played an animated hero in one project and a morally ambiguous manipulator in another. He’s done high-profile procedurals (Criminal Minds, Law & Order: SVU) and indie dramas with small crews and limited budgets. It was Lost that gave him legitimacy, but it was the darker material that stuck. “I think people saw a young actor who could go to those dark places,” he says.

“Those roles have stayed with me. The more broken the character, the richer the canvas. My favorite thing is digging deep and finding the humanity where most people wouldn’t expect it.”

He credits some of his on-set education to directors like Holly Dale, who worked with him on SVU and later on Law & Order: True Crime. Holly gave him room to experiment, but also shaped his performances with precision. “So much of what I know about television production is because of her,” Sterling says. That knowledge has proved useful well beyond acting, especially in producing.

Producing opportunities

His shift into producing came partly from studying the careers of people he admired. “Most of my idols, including Stallone, Pitt, Cruise, and Witherspoon, built their careers by creating their own opportunities,” he says. During the pandemic, when most productions had stalled, he teamed up with filmmakers Garrett and Brandon Baer to create Don’t Log Off, a “screen-life” thriller told entirely through digital windows. The stripped-down format was a necessity, created during lockdown, but it also presented a creative challenge. “It’s all about story and character development, with very little to hide behind,” he says. As a producer, he saw his role as clearing a path for the director:

“Whether that’s talent, financing, or production resources. Finding the balance is much easier when you fully trust the people you’re working with.”

That ethos carries into Shattered Ice, his upcoming drama set in the insulated world of New England high school hockey. The film follows Will Mankus in the aftermath of his best friend Danny Campbell’s death by suicide, the character played by Sterling. Through flashbacks, audiences come to see that Danny’s confident exterior masked deeper struggles.

“Even people who seem to have it all together can be struggling,” Sterling says. A lifelong hockey player himself, he was drawn to the project both for its subject matter and for the potential to spark conversations about mental health in spaces where vulnerability is often discouraged.

Hockey, he points out, is paradoxical: an aggressive sport with one of the most supportive communities he’s known.

“Both acting and hockey are tight-knit, but also competitive. It’s easy to put up walls. But you can’t win a game, or make a great movie, by yourself. When you allow yourself to be vulnerable, people will relate to you.”

Adapting to the industry

Sterling’s awareness extends to how he thinks about the industry itself. He’s been around long enough to see seismic shifts in how stories are made and distributed. He was part of Netflix’s The Killing in its early years, when streaming still carried an air of novelty and skepticism. “The same doubts existed around social media and vertical content,” he says. “Now those formats dominate the landscape.” His view is pragmatic: “Adapt or die,” he says, quoting Brad Pitt’s Moneyball.

Adaptation, for him, also means protecting his mental well-being in a profession that demands constant reinvention. Hockey is his escape, offering exercise, community, and a space where the stakes feel different. “Skating is one of the best forms of therapy for me,” he says. “Plus, the hockey community is always there for you.” Off the ice, he keeps a circle of people he trusts and reminds himself that one yes can cancel out years of rejection.

When asked about his dream project, Sterling doesn’t hesitate, listing filmmakers such as Scorsese and Gaspar Noé, along with genres including action films he has yet to tackle. But there’s also a quieter ambition: to keep working, to keep making things that resonate enough to get made in a climate where even bankable projects can stall.

“It’s harder than ever to get films made. So anything that resonates with the community enough to get support feels like a win.”

Constant commitment

In a way, that’s the throughline from his earliest days on Lost to the projects he’s producing now. Whether it’s a pandemic-born indie with a cast on Zoom, a sports drama probing mental health, or a network procedural with a carefully calibrated villain, the constant is the same: full commitment.

“When you fully commit, you can make something great no matter the circumstances. Lean into your strengths and use what you have.”

It’s an approach that has kept him working across genres, platforms, and roles in an industry where careers are often defined by a single hit or a single season. For Sterling Beaumon, the game is not just about landing the next job; it is about building a body of work that feels deliberate, varied, and, above all, alive.

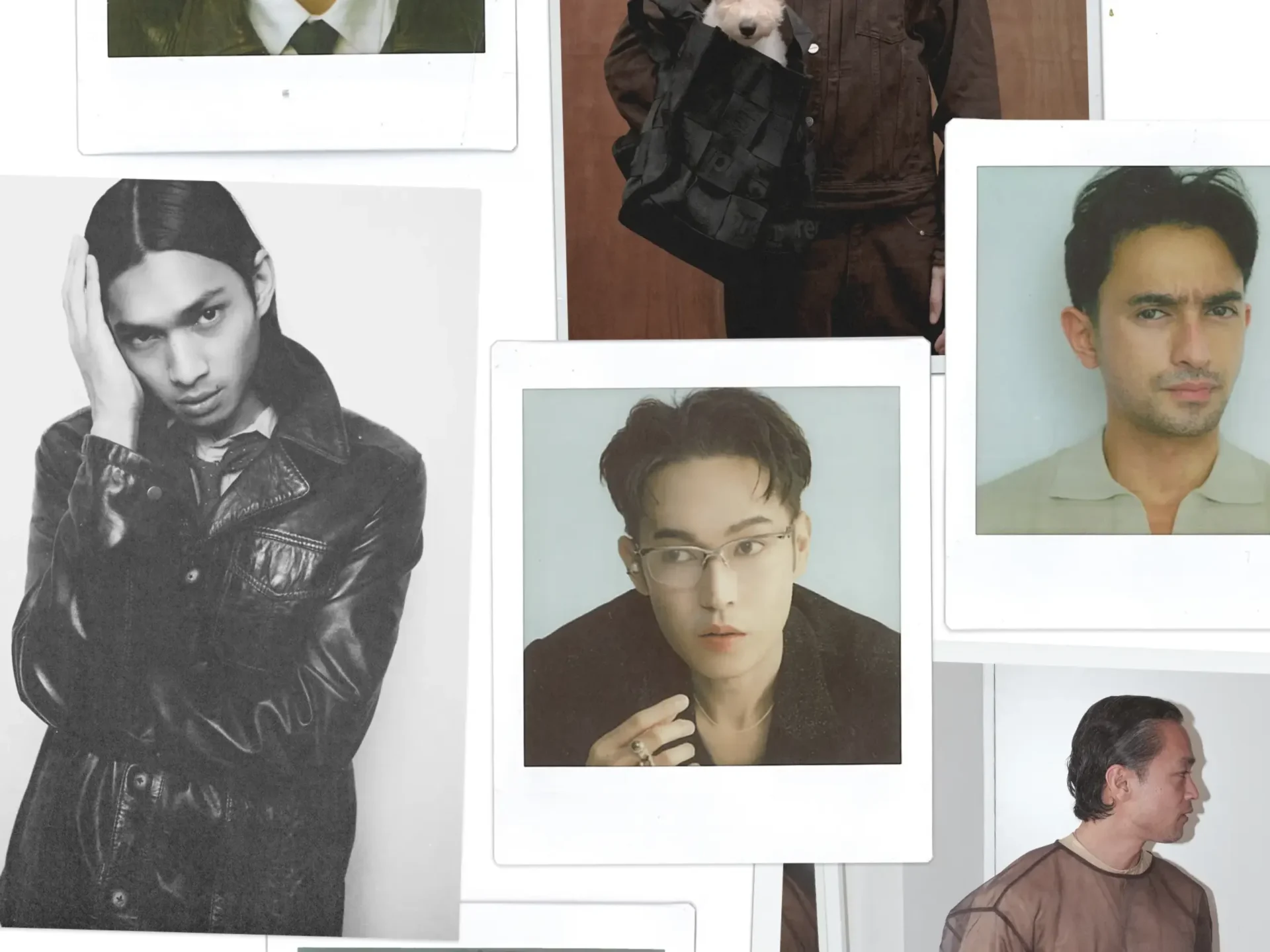

Photography Isaac Alvarez