Lav Diaz’s Magellan Just Rewrote History—and Gael García Bernal Is Steering the Ship

In Lav Diaz’s Magellan, Gael García Bernal steps into the role of the infamous explorer in a haunting epic that reclaims Southeast Asian history from the margins of empire

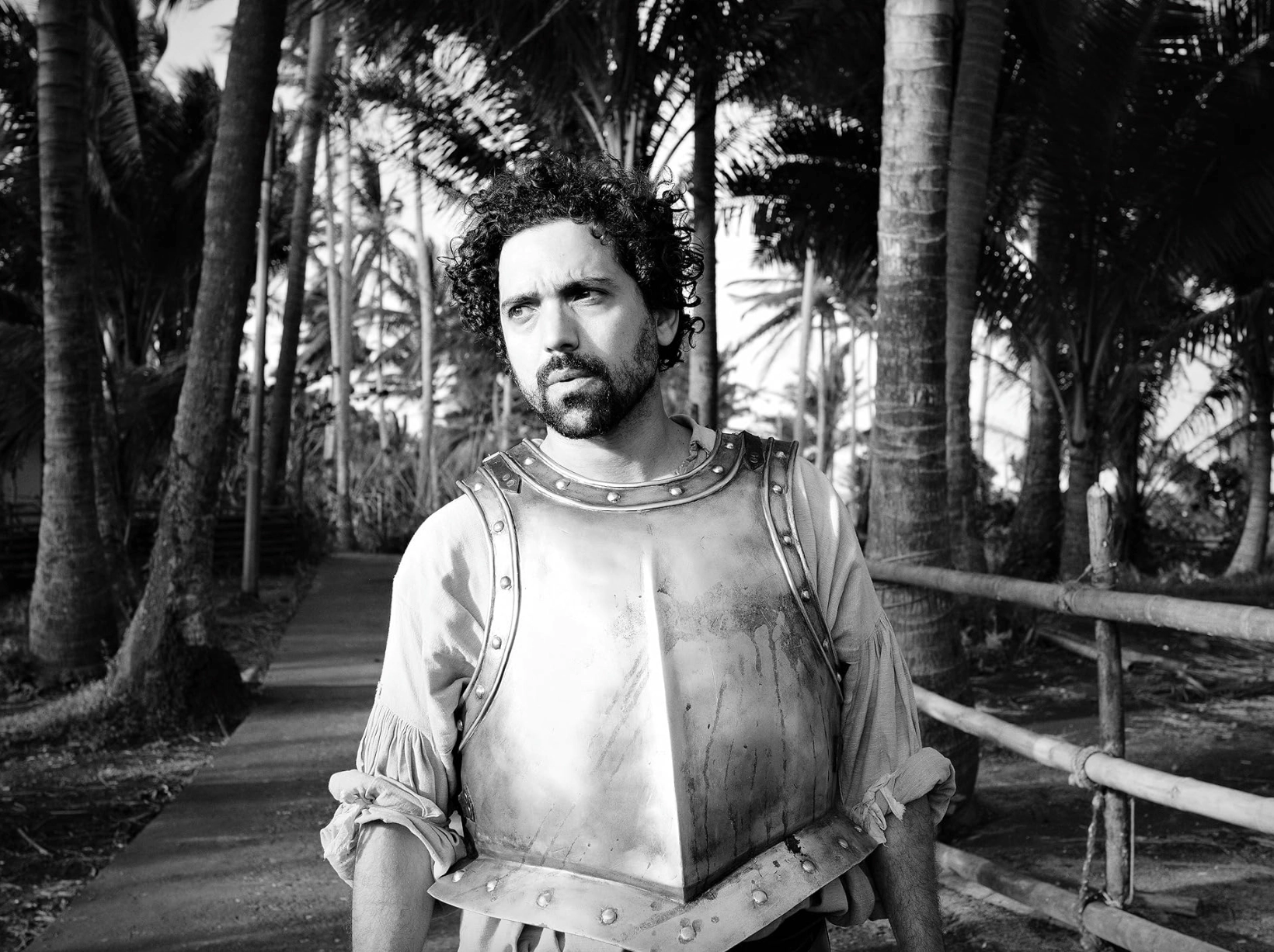

Lav Diaz’s much-anticipated Magellan premiered in the Cannes Premiere section on the 18th of May, steering audiences through an uncharted retelling of 16th‑century history. The Filipino director, renowned for epic slow-cinema like Norte, the End of History, has transformed the saga of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan into an intimate examination of empire and faith. Starring Gael García Bernal as Magellan, the film unfolds largely in the Philippines and Spain, revisiting the Spanish and Portuguese colonial campaigns in Southeast Asia.

Upon its debut at Cannes’s Debussy Theatre, Magellan earned a five-minute standing ovation, evidence that even at nearly three hours (Lav’s shortest cut to date), its haunting portrait of a man facing his own demons resonated deeply.

ALSO READ: The Verdict Is In. Here’s What People Are Saying About Cannes’ Most Anticipated Films

Even in these early screenings, critics have picked up on Magellan’s unique reframing. Rather than an adventure yarn, Lav offers a sombre epic: villagers on a Philippine shore exult in the coming of the white man one moment, only for the camera to cut to dozens of faceless bodies washed up on a shore after an unshown battle. This jagged opening sets the tone, scenes of colonial violence are shown only in aftermath, the camera lingering on nameless corpses like tableaux of silent accusation. The film thus holds the insidiousness of colonization up to the light, probing the agony of loss and the anguished faith of indigenous characters who find themselves abandoned by both prophecy and empire.

In Lav’s vision, Magellan’s voyage across the Pacific becomes less a quest for glory and more a slow unraveling of moral consequence. The hero is a distant figure, Gael’s performance gains strength precisely from how detached and flesh-and-blood Magellan feels from the carnage unfolding around him, and the film often refuses the full spectacle. Battles are notably off-screen; instead we behold the aftermath of violence, a village floor strewn with bodies hinting at brutality to which these blasé figures have long been numb.

Slow cinema, fast history

This austere approach reflects Lav’s signature style. Known for multi-hour narratives shot in languid black-and-white, he has made Magellan (shot in color) one of his shortest films, trimmed from a colossal nine-hour final cut. Yet the slow-cinema-shaped asterisk remains: scenes unfold like elaborate sketches, each one a painterly composition that resembles paintings more than anything to the camera’s eye. Lav himself emphasizes that Magellan is no orthodox biopic. He said in an interview that the story will “no longer be told from the Europeans’ perspective” but reframed “from the Southeast Asian point of view,” explicitly balancing out the traditional white man narrative of history.

In interviews, he stresses that his intent is conceptual rather than strictly factual. Magellan (in film) even speaks Spanish rather than Portuguese, an odd choice Lav implies is inconsequential to his conceptual design.

After eight years of research, Lav emerged with a bold reinterpretation that directly challenges Philippine national mythmaking. Most notoriously, Magellan flatly dismisses the legendary figure of Lapu‑Lapu, who in Philippine lore is the tribal leader said to have killed Magellan. Lav asserts in interviews that “there is no Lapu‑Lapu”, a “myth” he attributes to later nationalist invention.

In Cannes he defended this stance bluntly, “We need to start discussing that… I think I’m near the truth. It is going to be controversial in our country, but we need to have a dialogue about the past.” As he put it elsewhere, the “greatest pathology of the Filipino is our mythmaking” and Magellan is meant to prod audiences to “re-examine our past” continuously. The film thus becomes a forum for the filmmaker’s own historiography: political, revisionist, and insistently postcolonial.

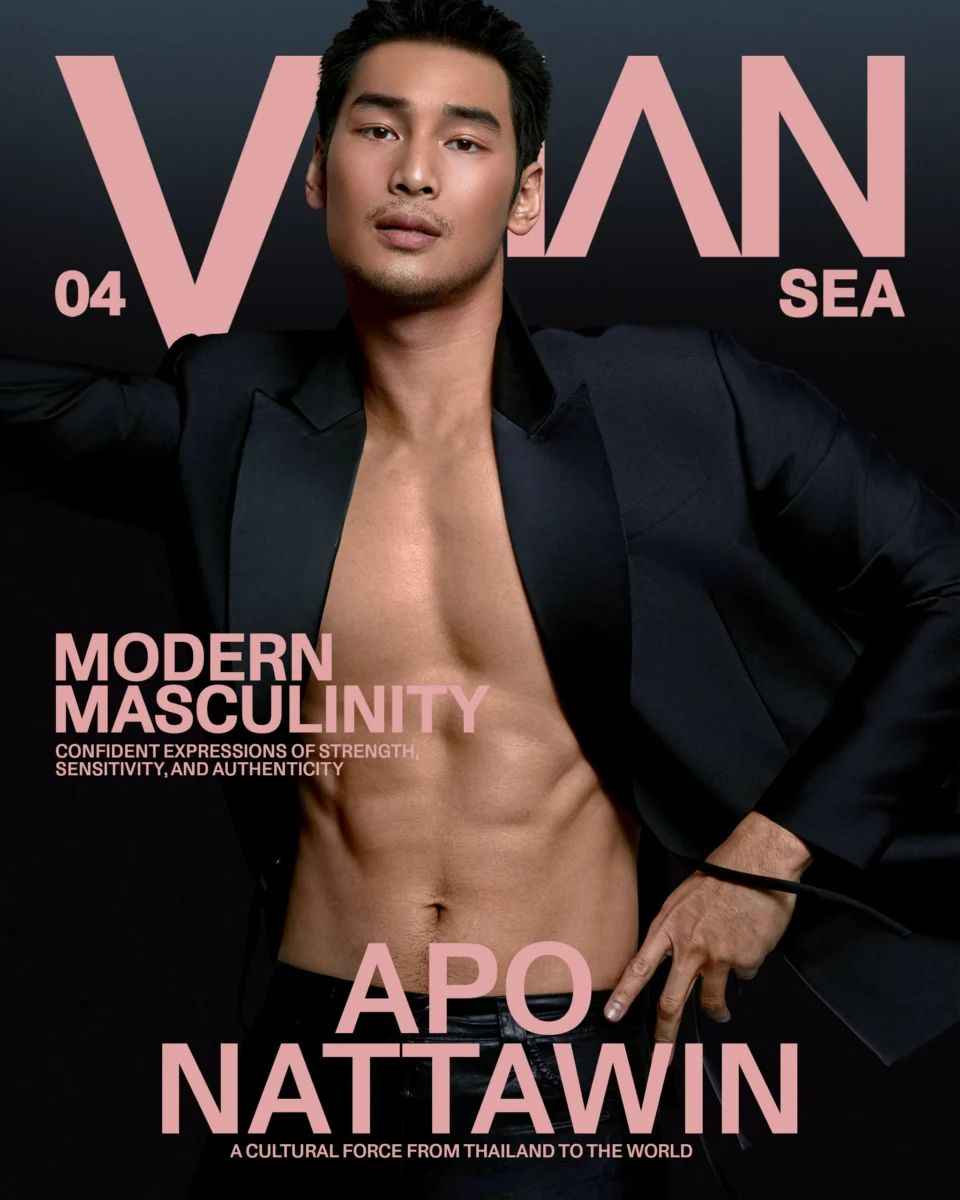

Casting the explorer

Central to this vision is Lav’s casting of Mexican actor Gael in the titular role. Gael is an artist of cosmopolitan pedigree, as one Argentine reviewer wryly notes, he’s “lost at sea in Lav’s haunting epic”, but he also carries his own history of revolutionary cinema. Lav recounts that Gael was “recommended” for the part, and immediately saw in him Magellan’s paradox: “cool, stubborn, intelligent, mysterious, distant, uncompromising, humble and imperial,” a mixture befitting the complex explorer.

That Magellan employs Gael to play a 16th-century Portuguese navigator is itself a telling choice. Critics have found his brooding presence fits Lav’s approach: “the flesh-and-blood manifestation of the violent colonial mentality.” One reviewer suggests that Lav’s oddly impassive hero points up the film’s deliberate repudiation of Magellan’s legacy, by keeping the character rather empty of ego or glory, the film “considers only death, not the circumstances leading up to it”.

Rewriting the map

The thematic implications of Magellan reach far beyond its festival audience. In this reimagining, Magellan’s signature feat, the first circumnavigation, is framed less as a heroic first contact than as a collision of worlds. Lav populates the frame with voices seldom heard in classic Age-of-Discovery tales: the Muslim rajahs Humabon and Colambu, Christian noble Juana of Cebu, and nameless islanders. We glimpse their rituals and their reactions to the invaders, though as one critic notes Lav generally avoids giving Euro-figures interior monologues. Magellan himself rarely speaks of motives beyond power and conversion.

Religion is thus recast as a mechanism of colonization. Scenes of prayer and conversion ceremonies unfold, counterpointed by silent tableaux of deaths on the shore, reminders of faith deployed as justification for conquest, and of conquest leaving behind only corpses.

In portraying the Philippines and broader Southeast Asia, Magellan resists exoticism. Lav reportedly did not give his non-professional local actors full scripts in advance, a working method that he argues brought out greater authenticity in their performances. And historically, he seeks to unravel accepted narratives: beyond doubting Lapu‑Lapu, he suggests European sources ignored or fabricated local agency.

For example, film narration notes that after Magellan’s death, Queen Juana of Cebu would be caught between allegiance to Spain and her own people, an angle rarely dramatized in textbooks. It’s a film deeply aware of how “the issue is always from the side of the white man” in conventional storytelling, to use Lav’s words, and it sets itself as a corrective by centering the subaltern gaze.

Cinematically, Magellan also marks a melding of worlds. Shot across Portugal, Spain and the Philippines, it is a true co‑production reflecting its titular character’s global reach. Many reviewers note that the film is at once classically composed and unhurried, a “hypnotic” experience, where only occasionally does the camera move with sweeping motion (perhaps a languid river shot or a slow push aboard the ship).

Otherwise Magellan favors static frame after static frame, each one a “fixed cinematic tableau” of history that lingers like a gallery piece. This formal rigor reinforces Lav’s critique: no glorified battle scenes are staged, and even the one sea-fight that appears is underexposed and distant, “anti-Master and Commander,” as one critic quipped, reminding us that this story is contemplative, not swashbuckling.

Beyond the compass

By revisiting Magellan with fresh eyes, Lav taps into broader cultural conversations. The film arrives as global cinema increasingly questions colonial-era myths. In Magellan, a 500-year-old voyage is not a celebration but a prompt for debate. The director himself has said Magellan forces us “to talk to people” and “be truthful and authentic about the past”. In doing so through art-house form, he exemplifies how cinema can transform a dusty historical tale into an unsettling experience.

As the dust settles on Cannes, the full journey of Magellan is yet to come. A longer version of the story is reportedly completed for later release, promising an even deeper dive into the tangled currents Lav glimpses here. But already the 2025 Magellan stands as a landmark, a Philippine auteur taking one of history’s most famous voyages and making it his own. It reorients the map, placing Southeast Asian landscapes and voices at the center of a global saga.

Lav’s Cannes entry is, in the words of one critic, “as immersive in a way that few decades-spanning stories successfully pull off”, a statement of faith that history, like cinema, must always be open to reinterpretation.

Photos courtesy IMDB, Cannes Film Festival, Instagram/Letterboxd