Southeast Asia’s Answers to the Black Tie

Across Southeast Asia, certain local garments are being embraced as counterparts to the Western black tie, with formal events accepting them as equivalents

What are the different kinds of formal wear in Southeast Asia?

Across Southeast Asia, certain local garments are already being embraced as equivalents to the Western black tie—so much so that weddings, events, state functions, and the like consider them as acceptable attire for black tie settings.

When styled and made properly, these clothes exude a confident air of formality that stands in step with sharp tailoring.

Here’s a breakdown per country:

Philippines – Barong Tagalog

The Philippines’ national garment—especially those made with piña (pineapple) fiber—is a staple at state functions, diplomatic events, weddings, and more.

The painstaking work required to extract fibers from pineapple and the elegant light champagne-gold hue of the resulting fabric elevate the barong to fine formalwear—as well as its value.

Indonesia – Beskap

The beskap is central to formal attire in Central Java in Indonesia, appearing in ceremonies such as weddings and court events. Typically made of thick and structured fabric, it’s tailored to fit closely to the body, giving it a formal and dignified look.

Defining features include a high standing collar, asymmetrical front buttons, and long sleeves that taper toward the wrist. It is typically paired with a sarong-style cloth wrapped around the lower body, traditional Javanese headgear, and a ceremonial dagger called a keris.

Malaysia – Baju Melayu

Across Malaysia, Brunei, and parts of Singapore and Indonesia, the baju melayu—the national dress for Malaysian men—is a key symbol of cultural identity and refinement.

It comprises two parts: the baju (shirt), which is a long-sleeved tunic that extends down to the hips or mid-thigh, typically with a high, stiff collar or round neckline with a single button; and the seluar (trousers), which are straight-cut and worn with a sarong-like cloth made of brocade or fine silk.

For formal events, the baju melayu is made from more luxurious fabrics like satin or silk. A songkok (traditional black cap) completes the attire.

Thailand – Suea Phraratchathan

The suea phraratchathan, which roughly translates to ‘royally bestowed shirt,’ is Thailand’s modern form of national dress for me. Created under the rule of King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) in the 1970s, it is designed as a practical yet dignified garment that bridges the gap between traditional Thai clothing and Western-style formalwear.

The garment, often a straight, loose-fitting shirt made of cotton, linen, or Thai silk, features a Mandarin-style stand collar, two to four patch pockets. Darker tones are often used for more formal occasions.

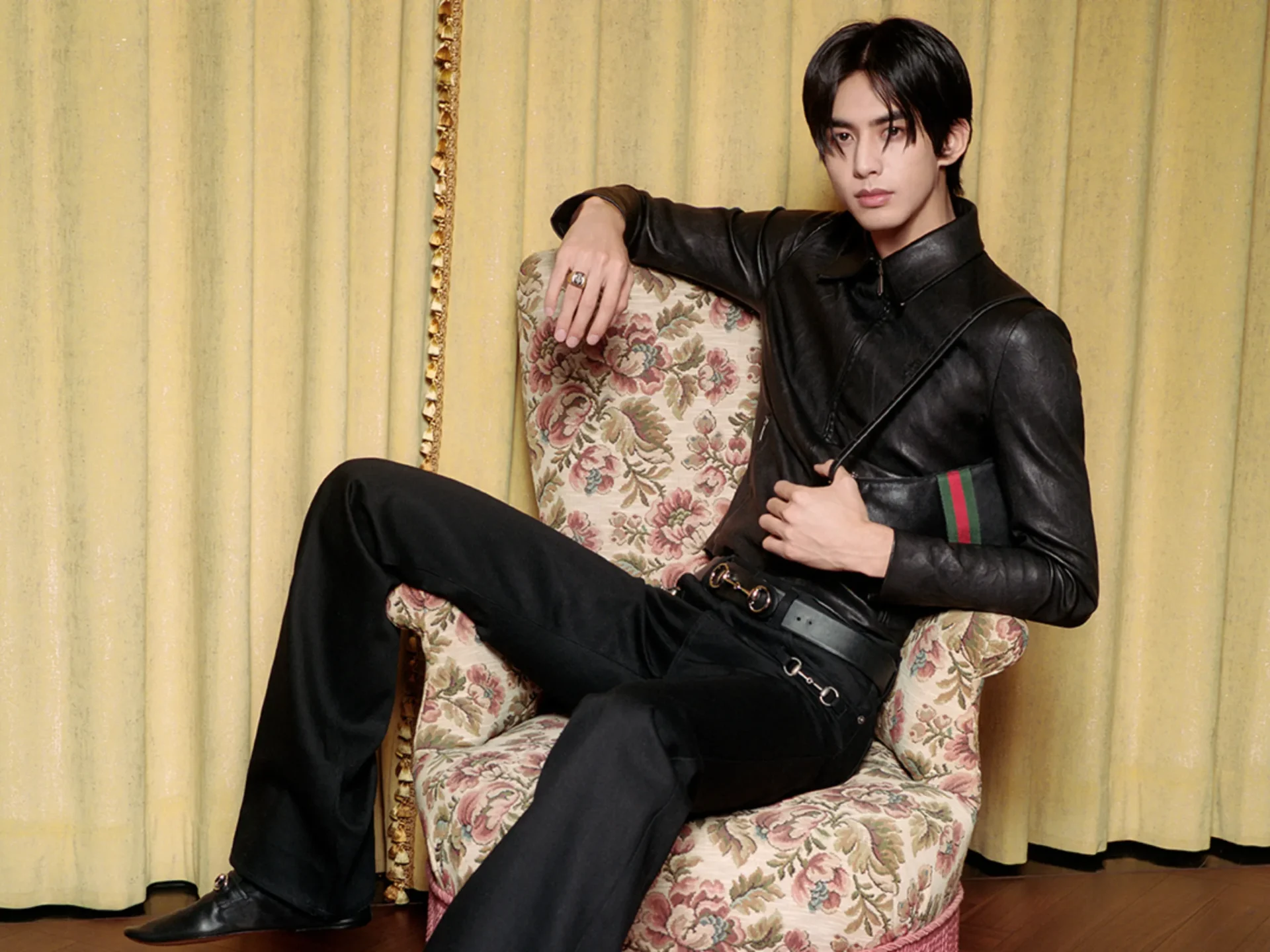

Vietnam – Ao Dai

The áo dài, the traditional formal attire for Vietnamese men, features a long, fitted tunic with a high Mandarin collar and side slits that extend from the waist to the hem, worn over straight-cut silk trousers. Worn during weddings, national celebrations, and cultural holidays, the garment if often made from silk or brocade, in regal tones like navy, crimson, or gold.

Southeast Asian garments are not just cultural markers — they are capable of standing in for black tie, especially when crafted with luxurious fabrics, tailored precisely, and worn with confidence. These pieces combine tradition, craftsmanship, and modern formality that honors heritage and style.

Banner photo courtesy Vietcharm Ao Dai House