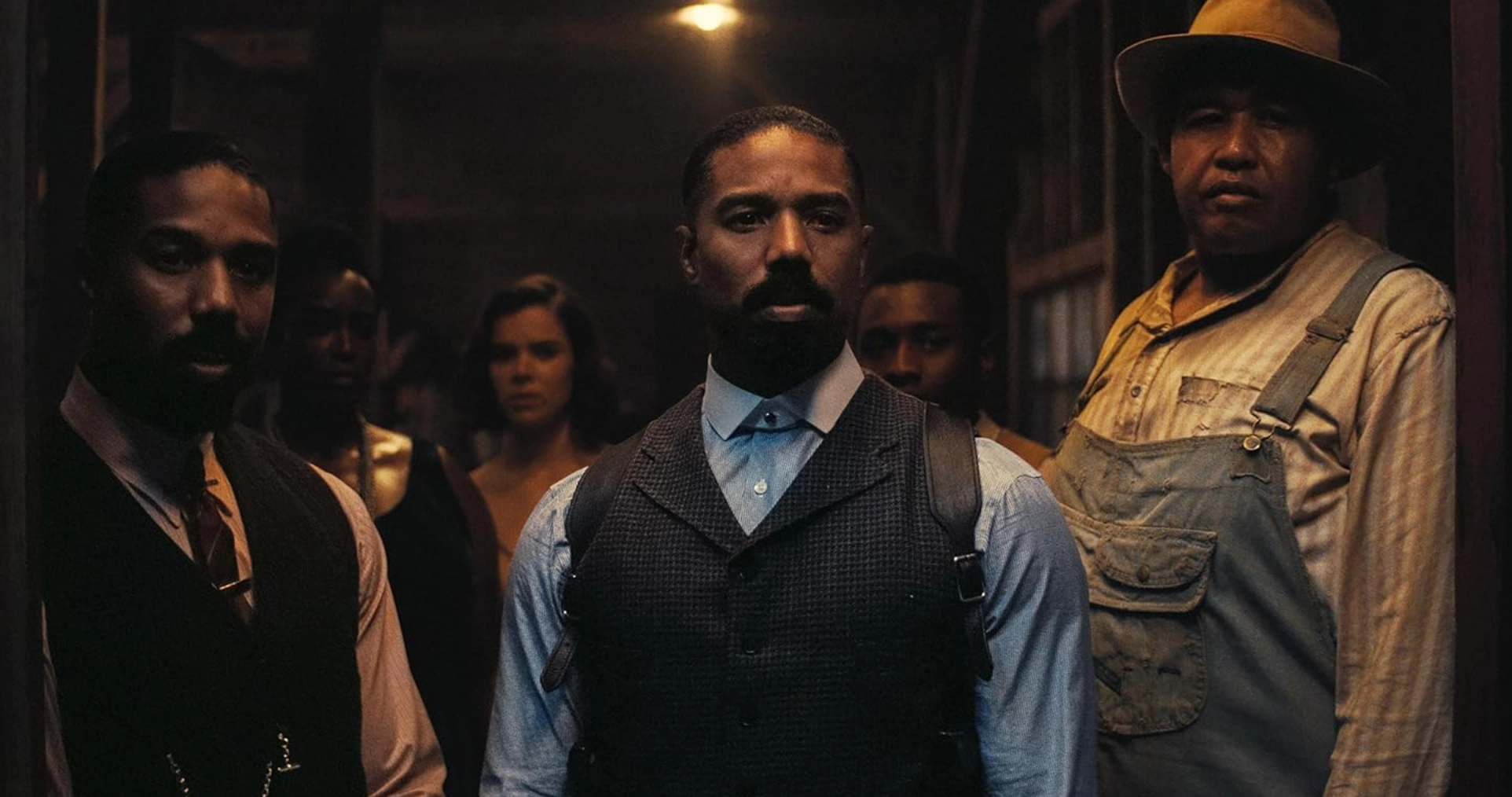

Inside the Sensual Apocalypse of ‘Sinners,’ Hollywood’s Most Original Hit in Years

Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan conjure a sultry, blood-soaked blues opera where Black style becomes salvation, and the monstrous is recast as myth

A new blockbuster, born of blood and blues

By now, you’ve either seen Sinners, the genre-breaking blues-vampire-musical epic from Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan, or you’ve been cornered at a brunch table by someone breathlessly trying to describe it: the sweat-drenched juke joint baptisms, the bone-rattling footwork of possessed Irish folk dancers, and the baritone sermons stitched with blood. “It’s Blade meets Porgy and Bess by way of Atlanta,” they’ll say, which feels at once accurate and a disservice to a film that refuses shorthand.

And yet, what’s most remarkable about Sinners is that it has succeeded. Not in the cautious, polite way “elevated horror” films are sometimes said to succeed, but in the language of true cultural impact: $122.5 million and counting, with word-of-mouth momentum most studio tentpoles would envy. Audiences have returned for second, even third viewings. Social media dissects Ryan’s shot compositions like sacred texts. Black Twitter has canonized Michael’s brooding, harmonica-playing antihero as the new Patron Saint of Charisma.

But to understand the full meaning of Sinners, you have to step outside of the numbers and into the cultural bloodstream. This is more than a film that made money; it’s a film that matters—and precisely now, when style, substance, and representation are converging in uncanny ways.

The timing is telling. This year’s Met Gala theme, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, offers a poetic echo of what Sinners is doing onscreen. The movie is, in many ways, the cinematic embodiment of that phrase. From the lacquered zoot suits of its vampire elders to the stitched-in ancestral memory of every costume design, Sinners is obsessed with the visual language of Black elegance and pain—how to wear both at once, and how to make it sing.

Reclaiming the monster

Much has already been said about Ryan’s genius for navigating pop culture’s twin poles: the personal and the mythic. But here, he’s doing something more mischievous and more dangerous. He’s daring to imagine Blackness as both vampiric and virtuous, blood-soaked and beatific. The film’s title is not a condemnation—it’s a reclamation. These “sinners” are not broken; they are defiant. Their sin is survival.

And survival, for Black creators in Hollywood, has always required transformation. It’s no coincidence that Ryan and Michael, collaborators five films deep, have chosen this moment to pivot away from the Marvel sheen and toward something murkier, more libidinal, more ungovernable. If Creed was about discipline and legacy, Sinners is about rupture and freedom. It asks: What happens when the archetypes we’ve inherited no longer fit? What happens when the monster is also the liberator?

Michael gives the performance of his career here—not because he’s louder or sadder or bloodier than before, but because he’s looser. His presence carries the uncoiled danger of an artist who knows the rules so well he’s begun to dismantle them. His vampire preacher is part Sam Cooke, part Huey Newton, all swaggering lament. In one unforgettable sequence, he delivers a monologue on the nature of hunger—not for blood, but for dignity—that feels like James Baldwin being channeled through a bassline.

A future stitched in velvet and blood

Critics and fans alike have noted how rare it is for an R-rated, original genre film to perform like this. But that’s missing the point. The real story is that Sinners is the rare movie that performs with purpose. It is cinema as style and self-fashioning, a box office hit that’s also a reckoning. It refuses to apologize for its aesthetic indulgences or political audacity. And audiences have responded—not because they’re tired of franchises (though they are), but because Sinners offers a communion those other films never promised: to see yourself in the dark and to still feel holy.

This is where the Met Gala tie-in doesn’t feel like a coincidence but a prophecy. As celebrities prepare to ascend the steps of the Metropolitan Museum clad in bespoke Black futurism, the cultural resonance of Sinners will be stitched into every exaggerated shoulder pad and gleaming gold tooth. The film is a mood board, a myth, and a mirror.

It has always been the case that style is survival. That Black style, in particular, is resistance wrapped in radiance. With Sinners, Ryan and Michael have not only made an unforgettable movie—they’ve made a statement: That the sinner, too, can be sacred. That the monster may, in fact, be the muse.

Photos courtesy IMDB