The Black Tie: Honoring Tradition, or An Outdated Practice?

Within Southeast Asia, the Western black tie code is widely accepted—but is it a form of honoring tradition, or is it an outdated colonial construct?

What does the black tie represent now amid changing attitudes toward style?

Outside the Western world, the black tie exists within a gray area.

Yes, it symbolizes formality, refinement, and respect—global codes understood regardless of language.

At the same time—especially in Southeast Asia, where the heat isn’t kind to multiple layers and thicker fabrics—the black tie somehow represents aesthetics from a colonial perspective. One would ask whether adhering to the code and insisting on this standard of elegance restricts aesthetic independence within the region.

For decades, especially during colonial periods, tuxedos and dinner jackets signified sophistication in cities like Manila, Jakarta, and Singapore, marking the wearer as globally fluent. They became equated to the upper class.

Yet as local identity and cultural pride gained ground, this Eurocentric uniform started to exist in parallel—oftentimes in, sometimes out of sync—with the region’s own clothing heritage.

Southeast Asian countries have been constantly renegotiating what ‘formal’ means. A growing number of Filipinos now attend black tie events in intricately woven barongs made from piña or jusi — as dignified as any tailored coat, but far better suited to the climate and culture. In Indonesia, hand-drawn batik tulis shirts in dark silk, paired with tailored trousers, have become accepted at gala dinners. In Malaysia, a well-fitting baju melayu in satin or brocade can command the same respect as a tuxedo.

These garments are not mere substitutes; they are cultural statements.

Still, the endurance of black tie in Southeast Asia isn’t entirely hollow. There is a reason luxury hotels and diplomatic functions continue to prescribe it: it provides a shared visual language of decorum. In multicultural, multi-faith cities like Singapore or Kuala Lumpur, where no single national dress dominates, the tuxedo remains a neutral baseline. It is elegant, but not culturally loaded. Especially for international events, it anchors the idea of formality in a way everyone can instantly recognize.

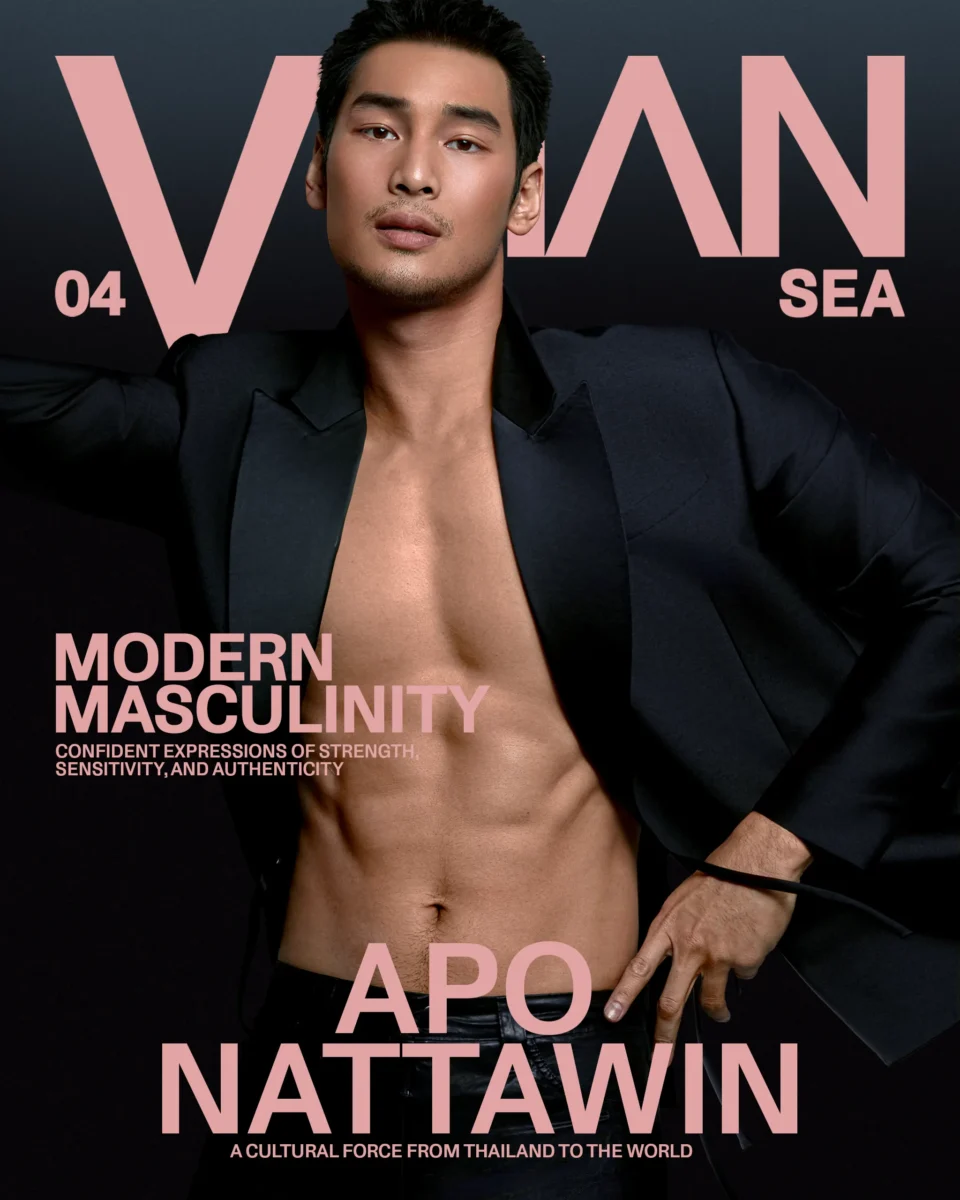

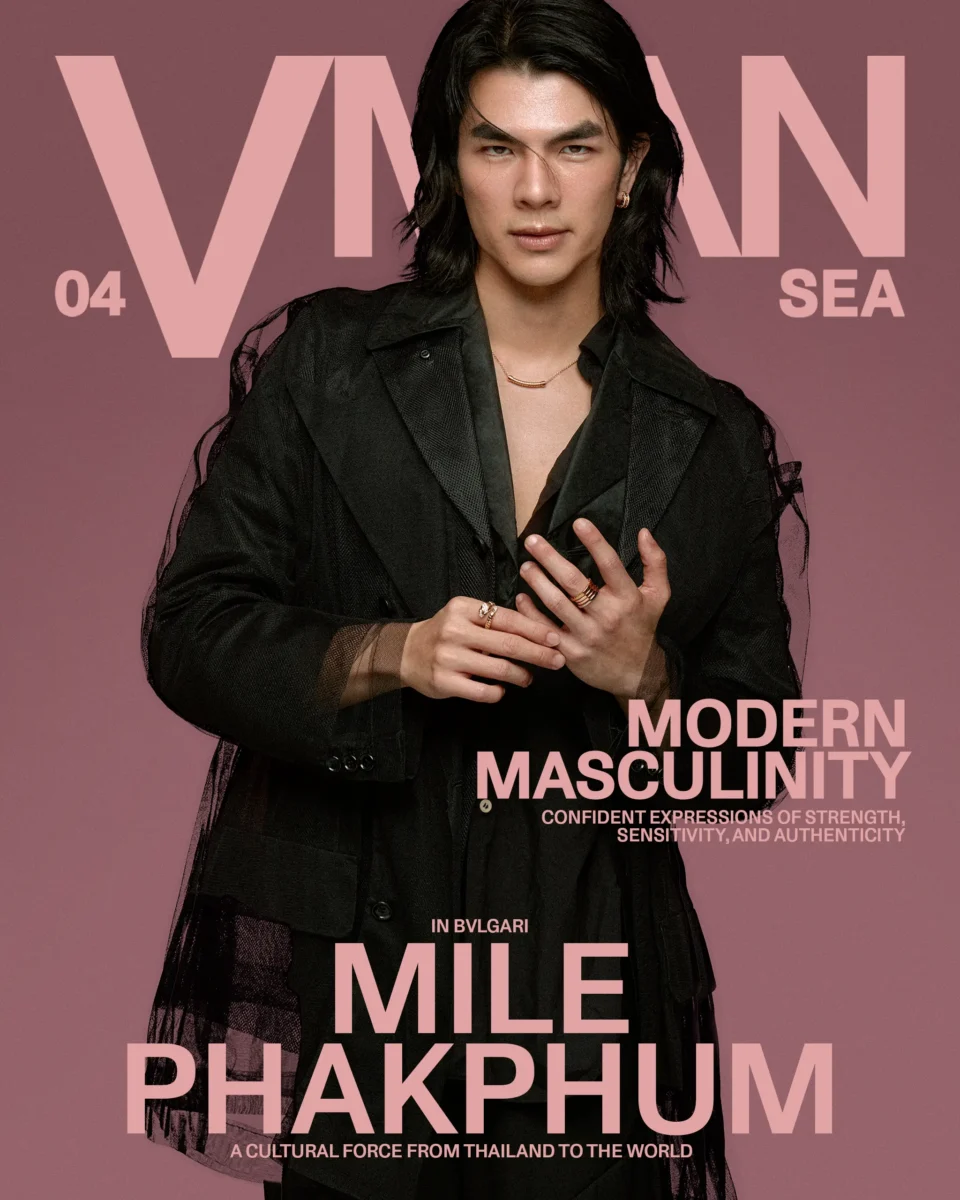

But formality is changing. Today’s designers are not discarding black tie — they’re dismantling it, from deconstructed suits, dinner jackets made with linen or tropical wool, cropped proportions, and mode. These reinterpretations look at the black tie code as a canvas for creativity.

The critique that black tie is outdated often comes down to its exclusivity — a system designed to enforce hierarchy through dress. In Southeast Asia, where formal wear historically came in the form of textiles (batik, barong, songket, silk), the tuxedo may feel disconcerting.

But modern perspectives suggest a compromise: honor the discipline of dressing well, without erasing context. The question is not whether black tie should disappear, but whether it can evolve.

In the end, the black tie survives not as a symbol of colonialism, but as a test of adaptation. It’s a tradition that has meaning only when reimagined — when the tuxedo sits alongside the barong, the batik shirt, the baju melayu, the raj jacket, and the áo dai. In that diversity, the region shows what true elegance means: not rigid adherence to old codes, but confident reinvention.