Not Another Teen Movie: 7 Coming-of-Age Films That Actually Get It Right

A curated list of seven coming-of-age films that explore the messy, intimate, and often overlooked corners of growing up

What’s inherently cinematic about the space between adolescence and adulthood is the blurry stretch of years when identity is more costume than character. It is here, in this emotional interim, that the coming-of-age film thrives; not just as genre, but as a mood. These stories don’t offer resolution so much as recognition of chaos, longing, and the beauty in the ordinary.

We know the usual suspects. Call Me by Your Name lingers like a perfume too often sprayed. But there is a deeper bench of films, messier, stranger, sometimes darker, that probe the emotional grammar of youth. Here are seven films that reshape the familiar narrative of coming of age with unexpected intimacy and bite.

The Miseducation of Cameron Post (2018, dir. Desiree Akhavan)

In the hands of a less careful director, this might have been a film about survival. But Desiree Akhavan steers clear of sensationalism. Chloe Grace Moretz plays Cameron, a girl sent to a conversion camp after being caught with her best friend. The setting is brutal, but the tone is unassuming, almost gentle in its defiance. It’s a story less about trauma than about rebellion; how connection forms in captivity, and how identity can persist even when suppressed.

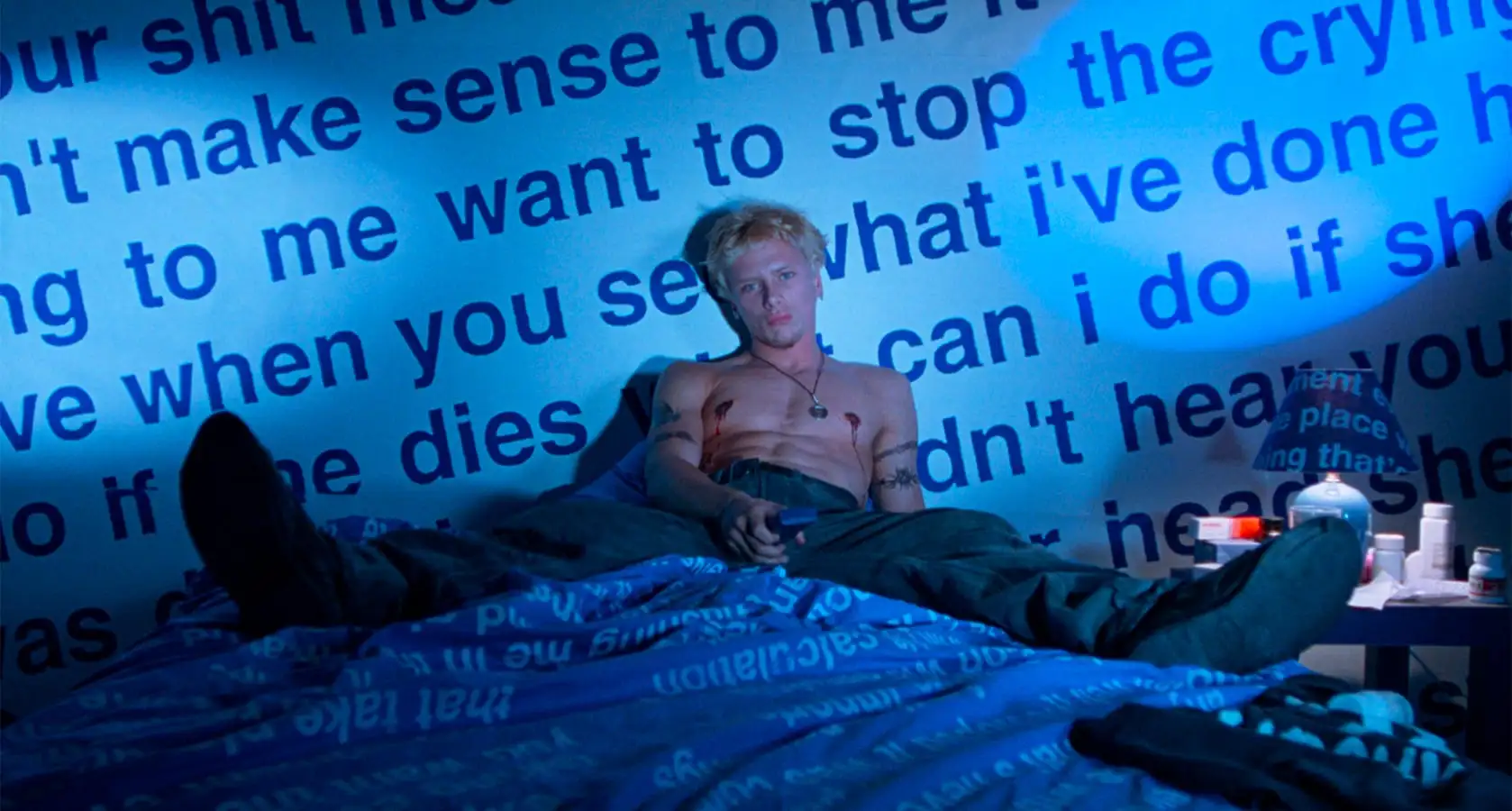

Nowhere (1997, dir. Gregg Araki)

If teenage life feels like the end of the world, Gregg Araki simply takes that metaphor literally. Nowhere is the apocalyptic sibling to Clueless: bright, violent, perverse, and chemically unhinged. Following a group of L.A. teens through one hyper-stylized day, the film is a neon hallucination, all alien abductions and bisexual longing. It’s campy and oddly profound. Gregg understood what many directors forget: that adolescence is inherently surreal.

The Way He Looks (2014, dir. Daniel Ribeiro)

Set in the humid stillness of São Paulo, Daniel Ribeiro’s film tells the story of Leonardo, a blind teenager who falls in love with a new classmate. The film is warm and luminous, tracing the contours of first love with patience and tenderness. What makes it revolutionary is how casually it treats disability and adolescence as overlapping realities, not plot devices. There’s no melodrama, just the slow unfolding of feeling.

The World of Us (2016, dir. Yoon Ga-eun)

At only 94 minutes, this Korean gem is a masterclass in emotional economy. It follows a ten-year-old girl navigating the brutal politics of girlhood, where friendships form and dissolve like weather. Yoon Ga-eun captures childhood not as a time of innocence, but of sharp cruelty and aching sincerity. The world here is not large, but it is immense, held entirely in the careful gestures of small betrayal and tentative hope.

Girlhood (Bande de filles, 2014, dir. Céline Sciamma)

Before Portrait of a Lady on Fire and Petite Maman, Céline Sciamma gave us this electrifying portrait of a Black teenager in the Parisian suburbs. Marieme, played by the magnetic Karidja Touré, breaks away from her suffocating home life to join a girl gang. What follows is not an indictment of rebellion, but a celebration of chosen identity. Céline’s camera doesn’t gawk or judge; it dances. One scene set to Rihanna’s Diamonds might be the most euphoric rendering of teenage freedom ever filmed.

The Myth of the American Sleepover (2010, dir. David Robert Mitchell)

Before he made It Follows, David Robert Mitchell delivered this understated indie about one summer night in suburban Detroit. The film meanders, like real memory, following multiple teenagers through parties, miscommunications, and small heartbreaks. It’s less about plot than about tone: the hazy light of streetlamps, the awkwardness of small talk, and the unbearable weight of wanting to be seen. It captures a particular melancholy, the sense that nothing important is happening, and yet everything is.

My Summer of Love (2004, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski)

Long before Cold War, Paweł Pawlikowski crafted this haunting tale of obsession and class division in the English countryside. Mona (Natalie Press), rough and working-class, meets Tamsin (Emily Blunt), rich and cruelly bored. What begins as romance becomes something stranger and more manipulative. This is not a love story. It’s a story about projection, about the danger of falling for who someone pretends to be. The film is lush and eerie, as seductive as it is suffocating.

There is no neat way to grow up. It is a process of sloughing off layers, wanting and withholding, performing and rejecting self. These films, in their strangeness and specificity, understand that. They are not aspirational. They do not flatter their subjects. Instead, they offer something rarer: the truth, in flickers and fragments.

Coming of age, after all, is not a genre. It is a wound, and sometimes, if you’re lucky, a poem.

Photos courtesy MUBI, IMDB, The Criterion Collection